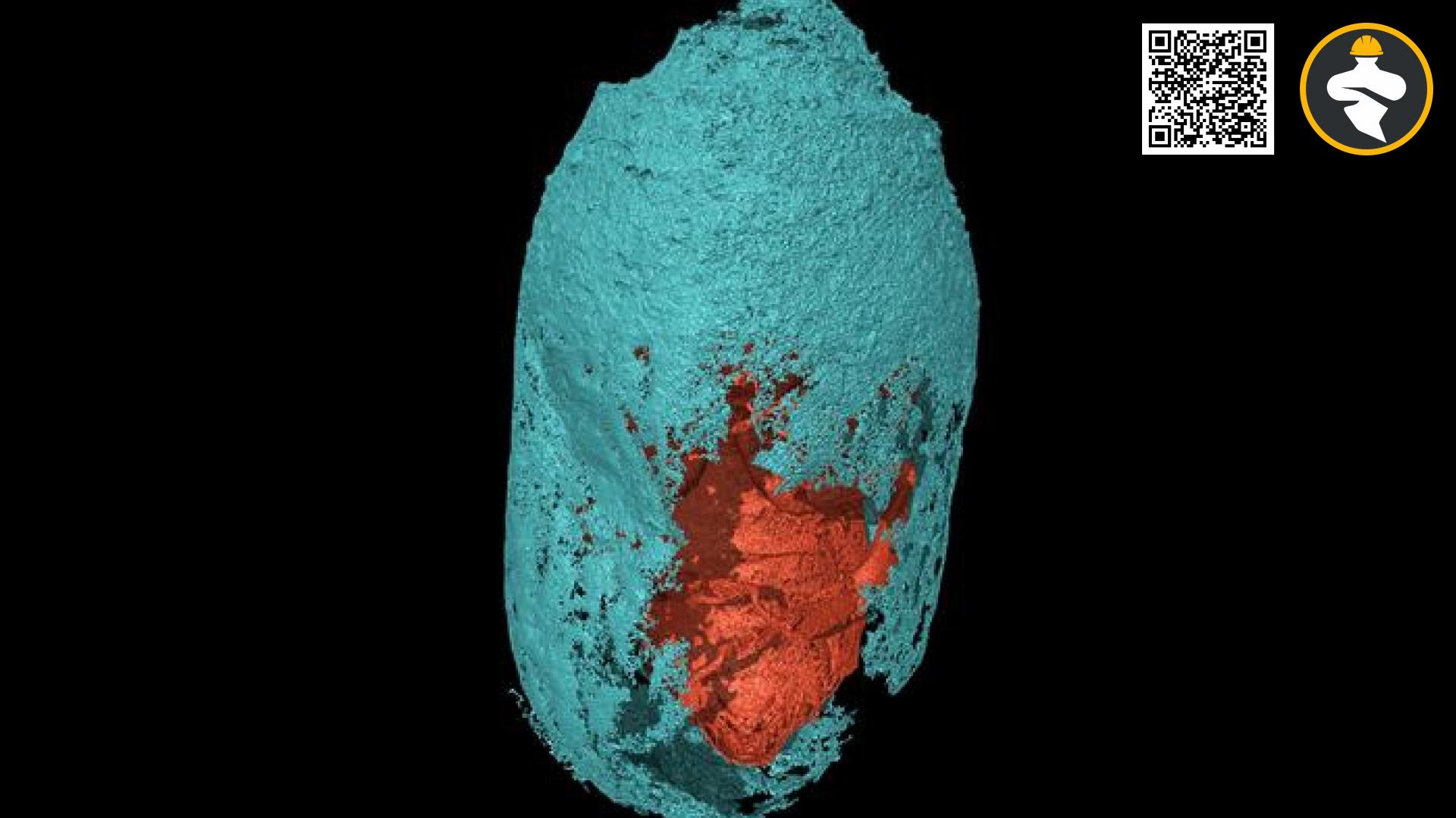

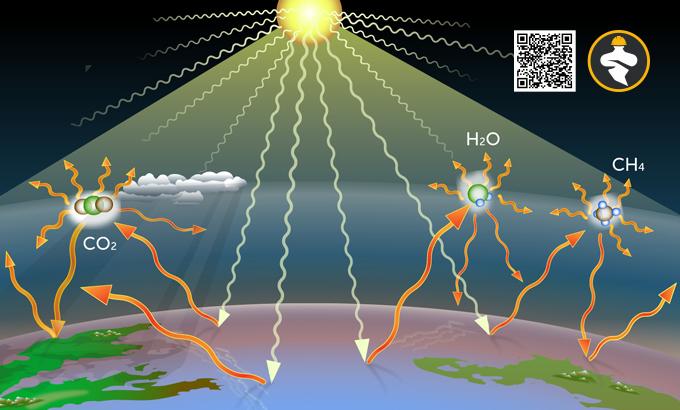

Between 930,000 and 813,000 years ago, our human ancestors faced a perilous moment in history, with their numbers dwindling precariously. This dramatic decline was set against the backdrop of a chilling period marked by severe cold and long droughts across Africa and Eurasia, as shown by geological records.

The latest DNA analyses suggest that only a handful of these survivors, hardened by the cold Stone Age, went on to become the forerunners of Homo sapiens, Neandertals, and Denisovans. The genesis of this common ancestral species is believed to have been between 700,000 and 500,000 years ago. Just a little before this, our ancestors had endured a frigid spell lasting approximately 117,000 years, with a mere 1,280 of them actively reproducing, narrowly averting extinction.

In more clement times, this breeding population was significantly larger, estimated to be between 58,600 and 135,000 individuals.

In an innovative twist, Hu’s team introduced a fresh statistical technique to deduce the sizes and timelines of these ancient populations. They drew from the genetic patterns seen in contemporary humans – specifically from a sample of 3,154 individuals spanning 10 African and 40 European and Asian populations.

Their findings reveal that the most fitting explanation for the current genetic diversity is a major population dip amongst our ancestors between 930,000 to 813,000 years ago. Particularly in Africans, the evidence for this ancient demographic crash was markedly pronounced. This suggests that by around 900,000 years ago, a reduced group of human ancestors had settled in Africa, though Eurasia remains a potential cradle for these resilient survivors.

Interestingly, Hu’s team postulates that members of this recovering population eventually evolved into H. heidelbergensis. Some scientists posit that H. heidelbergensis was a precursor to Denisovans, Neandertals, and H. sapiens, emerging around 700,000 years ago across both Africa and Eurasia. Yet, not everyone is in agreement, with some arguing that the varied skeletal structures attributed to H. heidelbergensis preclude it from being a single Homo species.

Two prominent figures, archaeologist Nick Ashton and paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer, cautiously acknowledge this hypothesis of an ancient population crash.

Still, they point out that the discovery of more and more fossils indicates the presence of diverse Homo groups across Africa, Asia, and Europe between 900,000 and 800,000 years ago, during this proposed population slump. Astonishingly, some of these groups, unrelated to modern H. sapiens, might have weathered the intense global freeze more effectively than their contemporaries linked to us.

To achieve clarity on these ancient population dynamics, we need DNA from ancient H. sapiens, Neandertals, and Denisovans, assert Ashton and Stringer.

The intriguing possibility, as per Hu and his team, is that these ancestral humans underwent a sharp decline in numbers, forming isolated groups that seldom interbred. However, a comprehensive understanding requires genetic studies that account for ancient variances in population size, density, range, and interbreeding dynamics, says population geneticist Aaron Ragsdale.

Stephan Schiffels, another population geneticist, remains skeptical of the study’s conclusions, questioning the precision of dating such ancient events and noting that no other studies have highlighted such a drastic ancient population drop.

However, Ziqian Hao, a study co-author, believes that drastic climate shifts might have pushed our ancestors and other species to the edge, or even beyond, of extinction. Supporting this, another study mentions a previously unknown cold phase in Europe causing a sharp decrease in hominid numbers around 1.1 million years ago.

In their ongoing quest, Hu and his team intend to delve deeper, integrating ancient hominid DNA and a broader modern human DNA sample, with a focus on Africa, to explore the rollercoaster of ancient population dynamics.

Reference: Bruce Bower@Sciencenews.org