Because ice cubes are less thick than water, they float. Researchers reveal in the Feb. 3 issue of Science that a new kind of ice has a density roughly comparable to that of water in a glass. If you could put this ice in your cup and it didn’t melt right away, it would bob around, neither floating nor sinking.

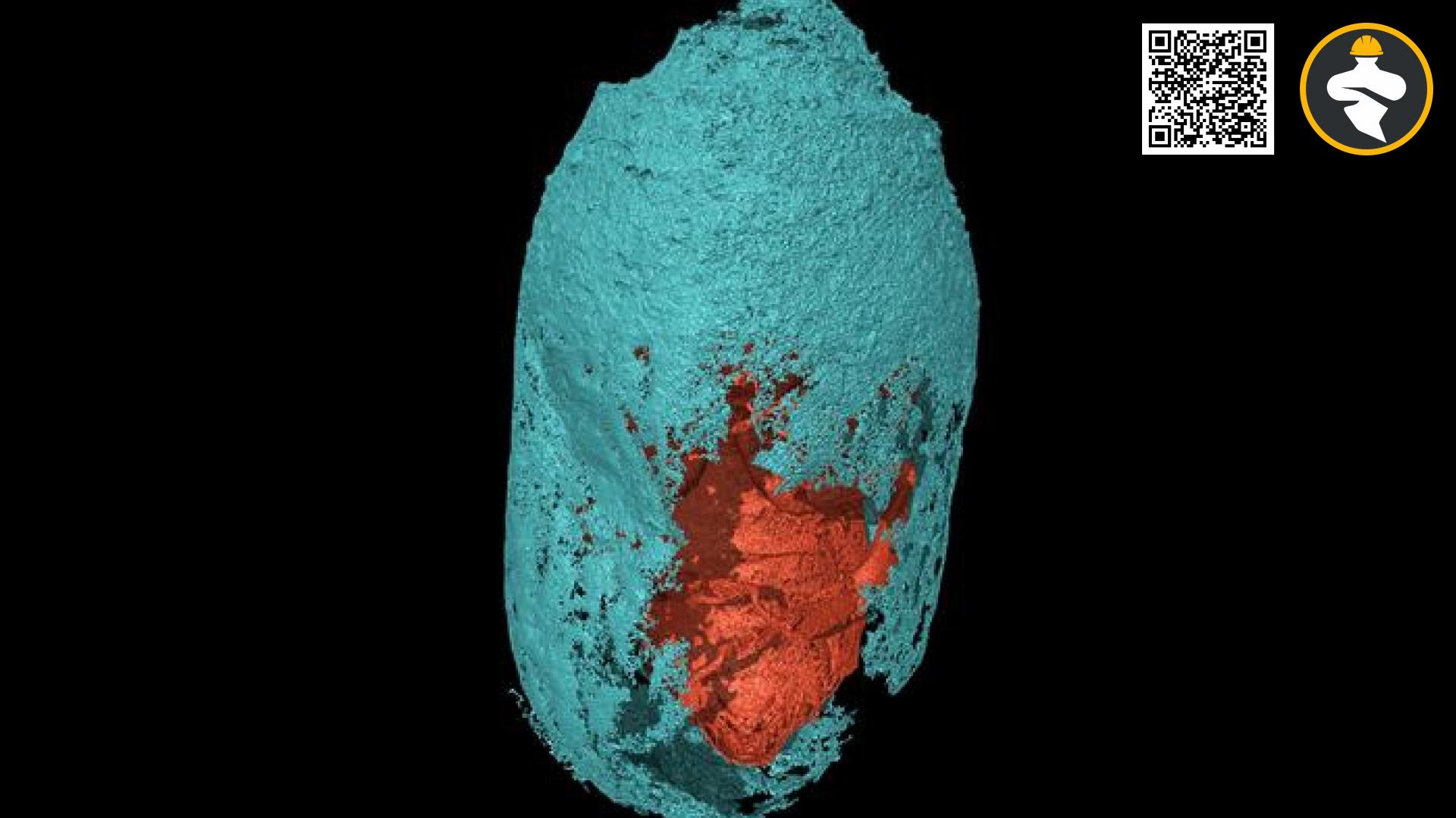

The new ice is a form known as amorphous ice. That is, the water molecules within it aren’t neatly ordered in a pattern like in conventional, crystalline ice. Other forms of amorphous ice are known, but their densities are either lower or greater than the density of water under typical circumstances. Some experts believe that the newly created amorphous ice will aid in the resolution of scientific puzzles.

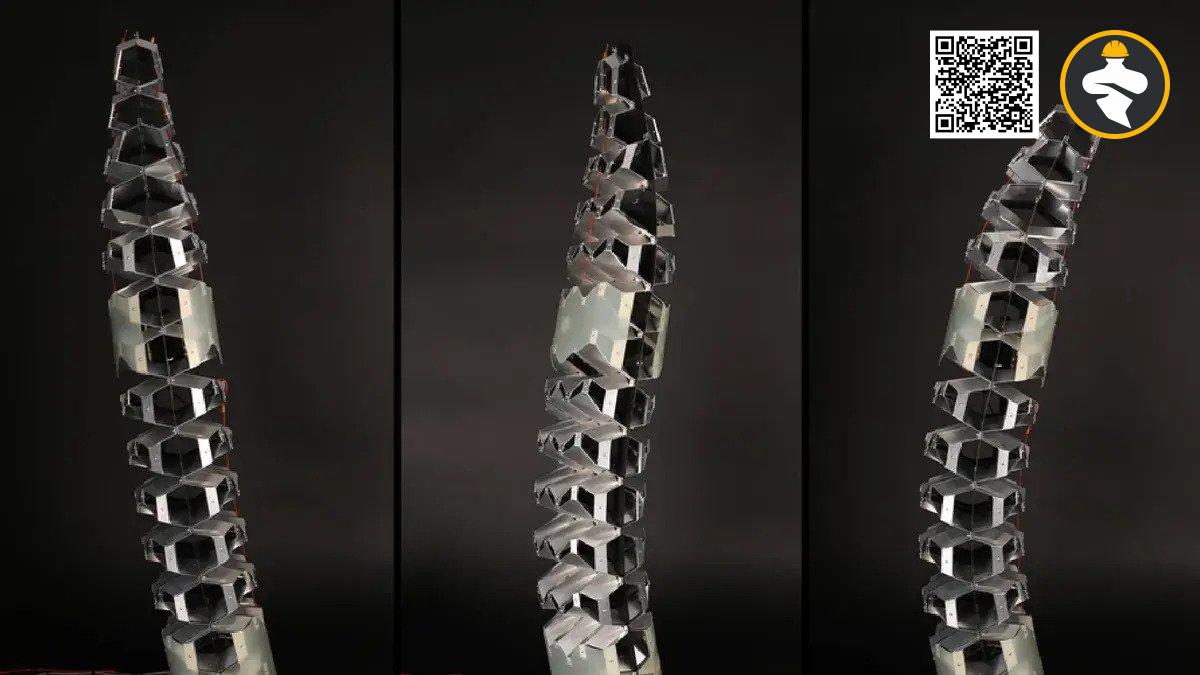

Scientists utilized a very simple process to create the new ice. Ball milling is the process of shaking a container of ice and stainless steel balls chilled to 77 kelvins (almost -200° Celsius). Curiosity drove the scientists; they had no idea that the process would produce a brand-new type of amorphous ice. “It was a sort of Friday afternoon concept we had, to simply give it a go and see what happens,” explains University College London physical scientist Christoph Salzmann.

An examination of how X-rays dispersed from the frozen substance revealed that they had developed amorphous ice.

In addition, computer models of the impacts of ball milling demonstrated that a disordered structure might be generated by layers of ice sliding past each other in random orientations in response to the stresses imposed by the balls.

“As a scientist, you have to be prepared for the unexpected,” says chemical physicist Anders Nilsson of Stockholm University, who was not involved in the study. He describes the ball milling technology as “very unique.”

According to Salzmann and colleagues, the new ice may actually be a unique type of water termed a glass. Glasses can be formed by rapidly chilling a liquid so that the molecules do not rearrange into a crystal structure. Glass in a windowpane is an example of this type of material, which is formed by cooling molten silica sand. However, other substances can also make glass.

If the new ice is in a glass state of water, scientists must figure out how it fits into the dual-liquid scenario. This might help scientists figure out what’s going on in the difficult-to-study supercooled settings.

However, other academics are doubtful that the new substance has anything to do with the strange physics of liquid water.

Physical scientist Thomas Loerting of the University of Innsbruck in Austria believes the ice is “closely connected to extremely minute, deformed ice crystals” rather than the liquid form of water.

Earlier computer models, however, revealed that water may form glasses with densities similar to liquid water, according to computational physicist Nicolas Giovambattista of the City University of New York’s Brooklyn College. According to Giovambattista, who was not engaged in the current research, the simulations created formations identical to those shown in the computer simulation of ball milling ice. “It offers up new avenues for investigation. “It’s new, so what exactly is it?”

Reference: Emily Conover @https://www.sciencenews.org