When a powerful tornado rips through a city, it frequently leaves behind wrecked buildings, shattered tree branches, and debris tracks. A comparably severe storm striking desolate, unvegetated country, on the other hand, is considerably more difficult to detect in the rearview mirror.

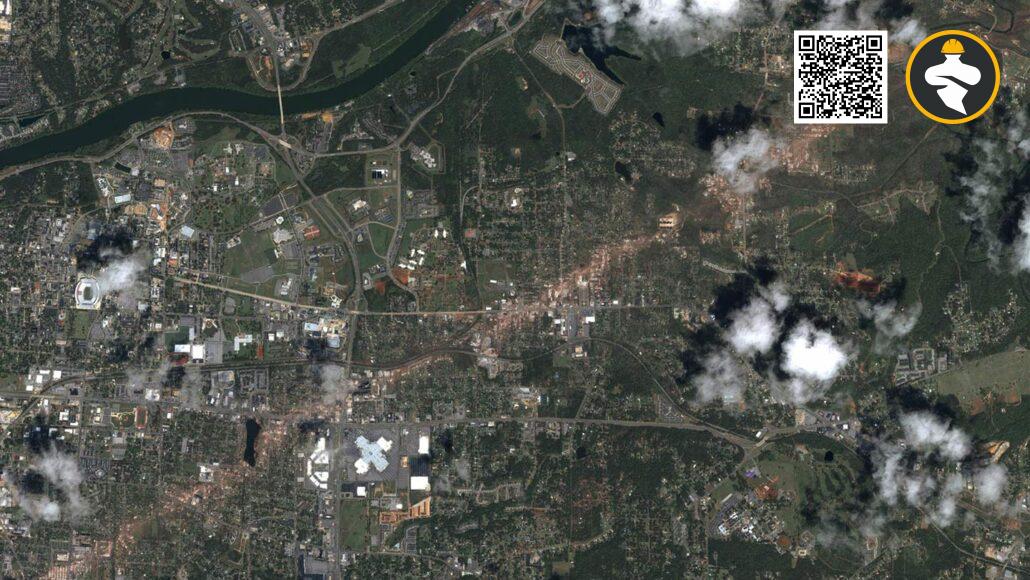

Satellite imaging has now shown a 60-kilometer-long trail of damp ground in Arkansas that was previously imperceptible to the naked eye. The structure was most likely dug by a tornado as it took away the topmost layer of the earth, researchers report in Geophysical Research Letters on March 28. The researchers believe that this strategy of searching for “hidden” tornado tracks is especially useful for better understanding storms that occur in the winter when there is less vegetation. Furthermore, current research indicates that the strength of winter storms is expected to rise as the climate warms.

According to the National Weather Service, about 1,000 tornadoes impact the United States each year. However, not all will be evaluated equally, according to Darrel Kingfield, a meteorologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, Colo., who was not involved in the research.

Storms that pass over inhabited regions, for example, are more likely to be studied. “Historically, there has been a pretty significant population bias,” Kingfield explains. Storms that occur over vegetated areas are very frequently researched because they leave visible scars on the terrain.

According to Kingfield, who has researched tornado-damaged woods, ripped-up grasses or felled trees act as beacons to signal the route of a storm.

Spring and summer are peak storm seasons in the United States, with more than 70% of tornadoes occurring between March and September, according to NOAA. On December 10, 2021, however, a series of storms began racing over the central and southern United States. Tornadoes that killed more than 80 people raced over cities and farms, much of which had already been harvested for the season.

Jingyu Wang, a physical geographer at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, and his colleagues set out to find the traces of such devastating storms in desolate, barren environments.

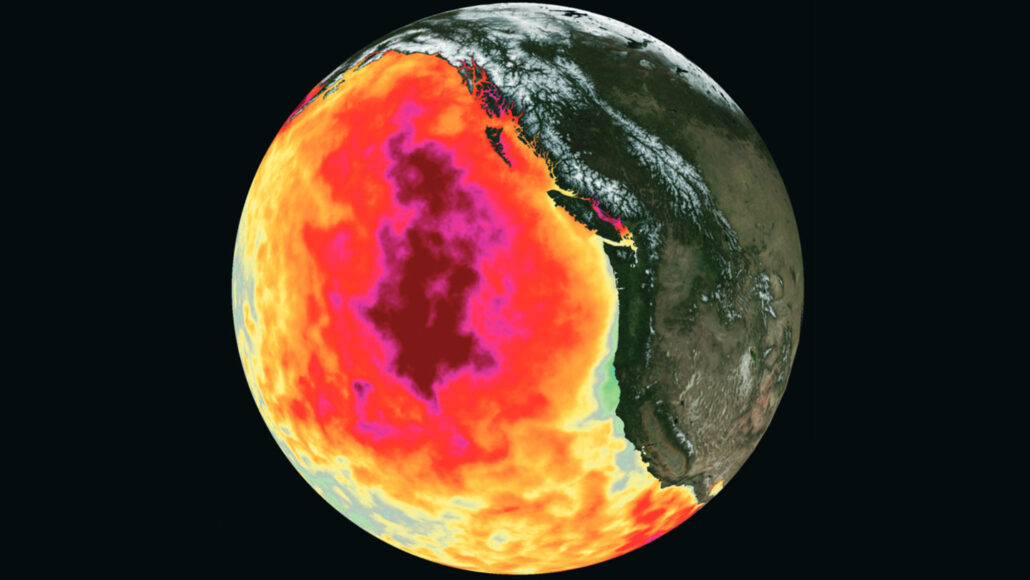

Even moderate gusts can suck up several cm of earth. And, because deeper layers of the earth are often wetter, a tornado should leave a clear signature: a broad strip of moister-than-usual soil. The texture and temperature of the soil, which are both related to its moisture content, influence how much near-infrared light it reflects.

Wang and his colleagues looked for changes in soil moisture associated with a passing tornado in near-infrared data obtained by NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites.

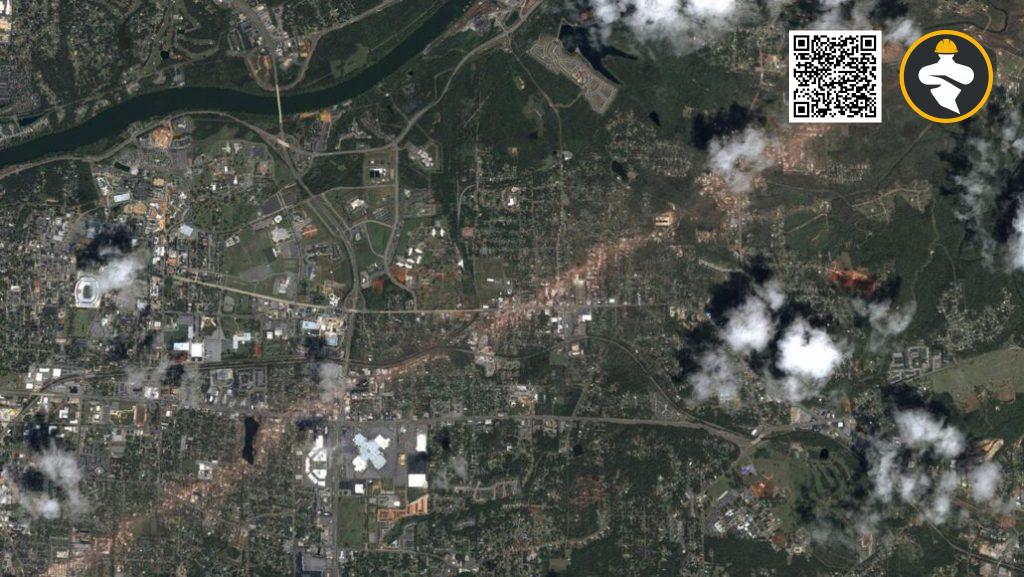

When the scientists examined data collected soon after the 2021 storm outbreak, they discovered a signal in northern Arkansas. The feature was consistent with a 60-kilometer-long wet dirt track.

Tornadoes had previously been observed in that location — just outside the city of Osceola — therefore the researchers decided that this feature was most likely caused by a violent storm.

That makes sense, according to Kingfield, and discoveries like this can uncover tornado characteristics that would otherwise go unnoticed. However, he emphasizes that this new strategy works best in areas where soils are capable of holding water. “You’ll need clay-rich soils.”

Nonetheless, Kingfield believes that these findings offer promise for investigating additional storms. It’s always helpful to have a new tool for predicting a storm’s severity, route, and structure, but many storms go unnoticed simply because of where and when they occur, he adds. “We now have this new ground truth.”

Reference: Katherine Kornei@www.sciencenews.org