The legendary Apollo lunar missions are frequently linked to high-visibility test flights, spectacular launches, and engineering marvels. But difficult, detailed handicraft, similar to weaving, was just as crucial to getting men to the moon. There were hundreds of thousands of men and women that worked on Apollo over a ten-year period in addition to Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and a few more names that we are all familiar with. These included the Navajo women who put together cutting-edge integrated circuits for the Apollo Guidance Computer and the Raytheon women who woven the computer’s main memory.

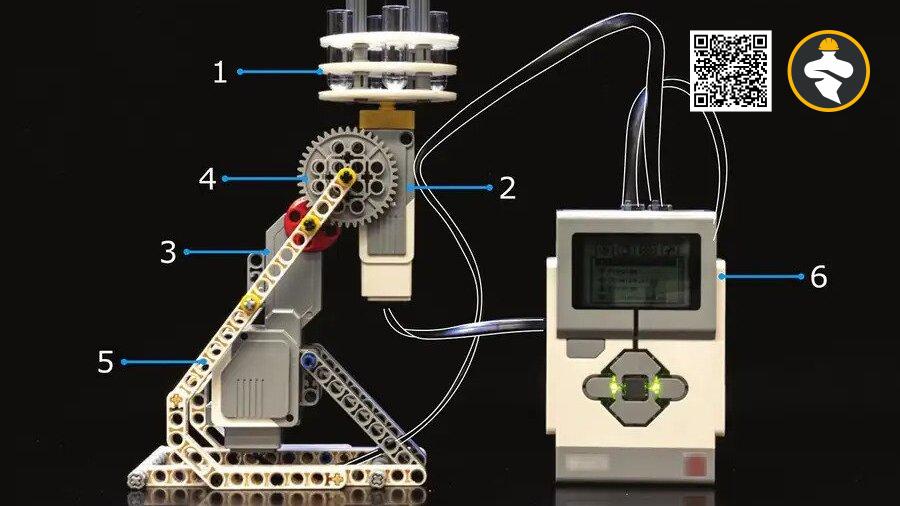

Computers were enormous mainframes that took up entire rooms when President John F. Kennedy proclaimed in 1962 that getting Americans to the moon should be NASA’s top priority. Hence, creating a highly stable, trustworthy, and portable computer to operate and maneuver the spaceship was one of the most difficult yet essential difficulties.

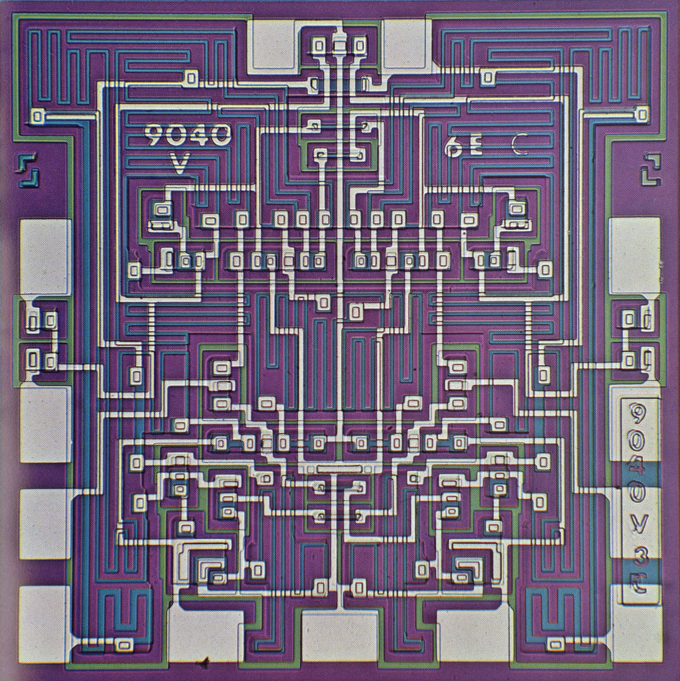

The Apollo Guidance Computer’s integrated circuits were selected by NASA to be state-of-the-art. These commercial circuits had just lately been launched. They were changing electronics and computing and played a role in the steady downsizing of computers from mainframes to modern smartphones. Fairchild Semiconductor, the initial Silicon Valley start-up, provided the circuits to NASA. In addition, Fairchild was a pioneer in the concept of outsourcing; in contrast to its 3,000 California employees, the business constructed a facility in Hong Kong in the early 1960s that by 1966 employed 5,000 people.

Fairchild was also looking for inexpensive labor in the US at the time. Fairchild established a facility near Shiprock, New Mexico, which is part of the Navajo reservation, in 1965, attracted by tax breaks and the prospect of a labor force with few other job options. At its height, the Fairchild factory employed over 1,000 people, the most of them were Navajo women who produced integrated circuits. It lasted until 1975.

It was a difficult task. In order to create intricate and varied patterns of lines and geometric shapes, electrical components had to be placed on tiny chips composed of a semiconductor, such as silicon, and connected by wires in certain areas. According to digital media expert Lisa Nakamura, the Navajo women’s work “was conducted using a microscope and needed meticulous attention to detail, great eyesight, high standards of quality, and intense focus.”

Fairchild made a direct comparison between the assembly of integrated circuits and rug-weaving, which the corporation depicted as the traditional, feminine, Indigenous skill, in a brochure marking the opening of the Shiprock plant. In the Shiprock brochure, images of a microchip, a rug with geometric patterns, and a woman weaving one were placed side by side. Nakamura contends that representation strengthened gender and racial prejudices. The job was disregarded as “women’s labour,” denying the Navajo women the proper acknowledgment and fair recompense for their efforts.

But as Nakamura points out, “the women who performed this labor did so for the same reason that women have performed factory labor for centuries—to survive.” Journalists and Fairchild employees also “depicted[ed] electronics manufacture as a high-tech version of blanket weaving performed by willing and skilled Indigenous women.”

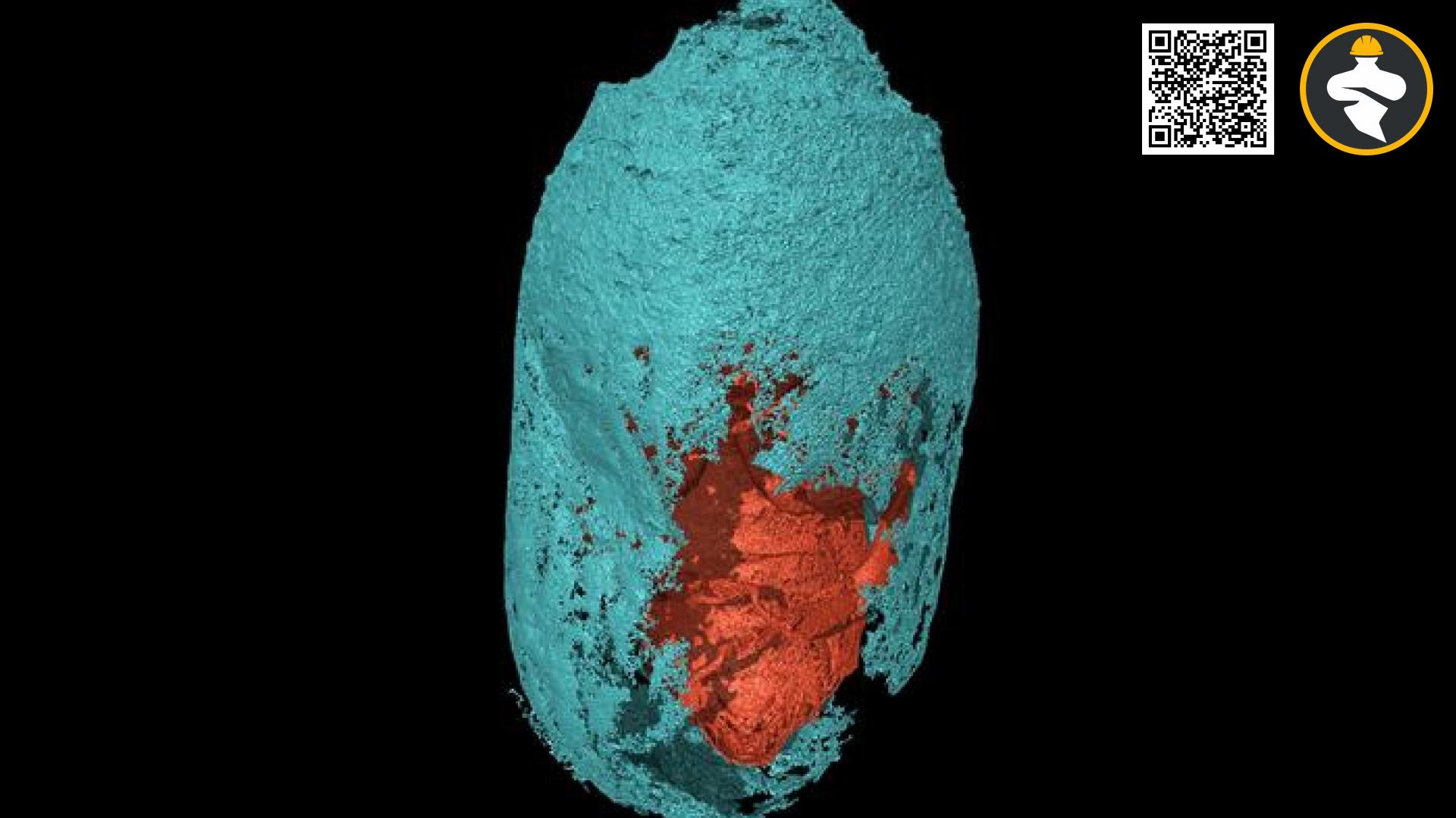

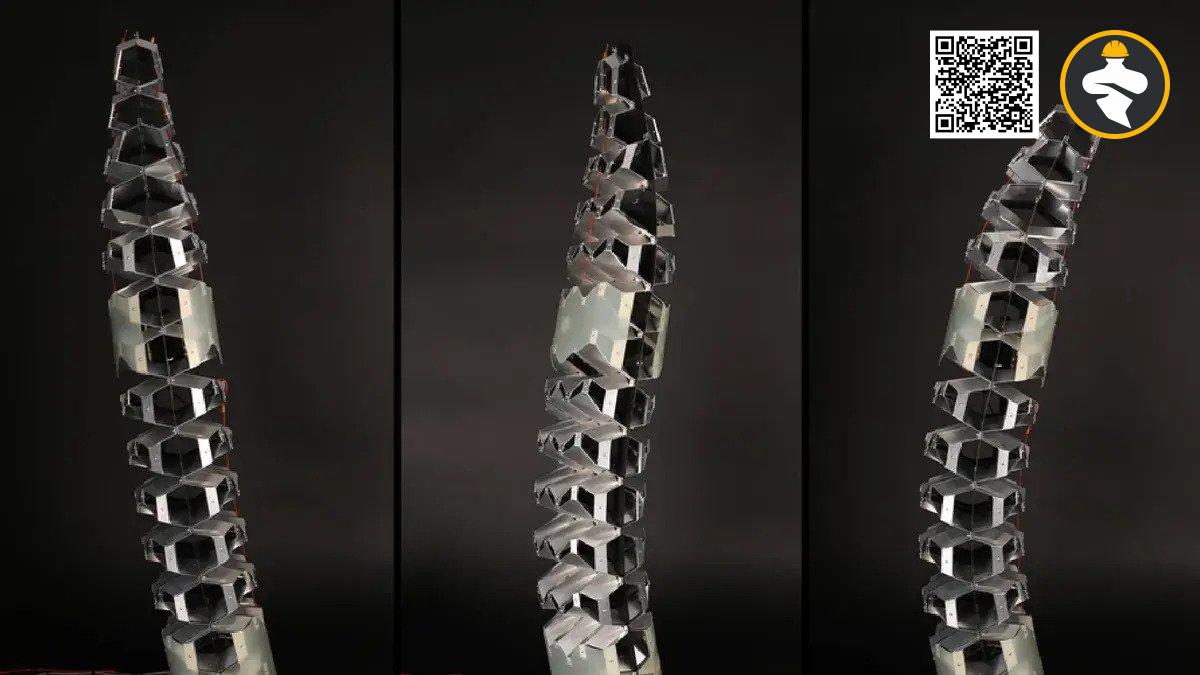

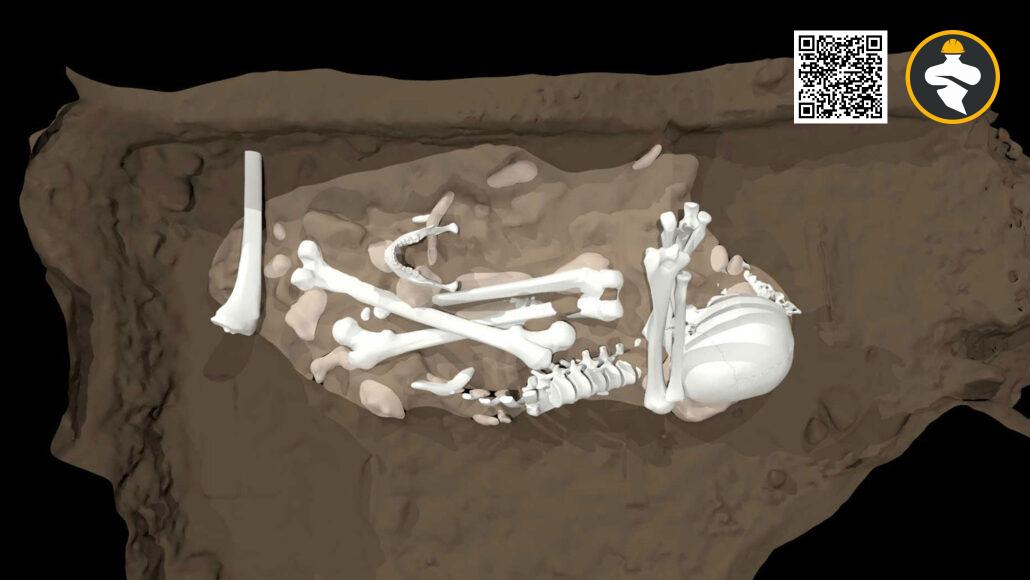

The main memory of the Apollo Guidance Computer was built by female Raytheon employees outside of Boston using a procedure that in this instance closely resembled weaving. A stable and compact method of storing Apollo’s computing instructions was once again required for the moon missions. Metal wires representing 1s and 0s were woven through tiny doughnut-shaped ferrite rings, or “cores,” in core memory. Women seated on opposite sides of a panel passed a wire-threaded needle back and forth to weave this entire core memory by hand in a certain pattern. (In other instances, a woman worked alone, threading the needle to herself through the panel.)

The “LOL” or “Little Old Ladies” approach was used by the Apollo engineers to create memory. Nonetheless, this work was so crucial to the mission that it underwent repeated testing and inspection. It took three or four individuals to review each component before it was approved, according to Mary Lou Rogers, an Apollo employee. For the federal government, we regularly had a team of inspectors check our work.

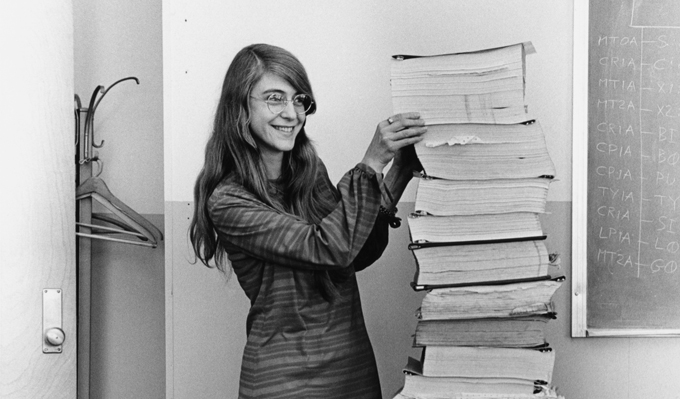

The “rope moms” who oversaw the formation of the core memory were also known as the “rope memory.” Margaret Hamilton is one rope mother about whom we know a lot. She has received numerous honors, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and is currently best known for overseeing the majority of the Apollo software. Her efforts, however, went hardly unnoticed at the time.

“Initial first, nobody thought software was that big of an issue,” Hamilton recalled. Yet with time, they came to see just how dependent they were on it. Life of the astronauts was in jeopardy. At any point during the mission, our software has to be extremely reliable and capable of seeing errors and recovering from them. The hardware also has to accommodate everything. Nevertheless, nothing is known about the tens of thousands of others who carried out this crucial labor of weaving core memory and integrated circuits.

At the time, Fairchild distinguished between the low-status and male labor of engineering and the work of the Navajo women by portraying it as a feminine skill. The work “came to be understood as affective labor, or a ‘labor of love,'” as Nakamura has written. Eldon Hall, who oversaw the hardware design for the Apollo Guidance Computer, also referred to the work done by Raytheon as “tender loving care.” This work was portrayed by journalists and even a Raytheon management as requiring little skill or thought.

In their Making Core Memory project, engineers Samantha Shorey, Daniela Rosner, Brock Craft, and Helen Remick, a quilt artist, recently disproved the idea that weaving core memory was a “no-brainer.” With the help of metal matrices, beads, and conductive threads, participants were invited to weave core memory “patches” in nine sessions, demonstrating the intense concentration and minute attention to detail needed. Then, the pieces were stitched together to create an electronic quilt that read aloud interviews with Raytheon managers and Apollo engineers from the 1960s. The disparity between masculine, high-status, well-paid science and engineering cognitive labor and feminine, low-status, low-paid manual labor was questioned by the Creating Core Memory project.

The Apollo computing systems were praised in a 1975 NASA study that detailed the Apollo missions, but none of the Navajo or Raytheon women were recognized. The assessment stated that the computer’s performance was faultless. The Apollo mission may have been most notable for its display of the computer software’s adaptability and versatility in terms of guiding, navigation, and control.

Many of women, especially women of color, contributed their professional, technical, and labor to that computer and that software. They were without a doubt women of science, and their little-known stories encourage us to reexamine who engages in science and what qualifies as scientific knowledge.

Reference: Joy Lisi Rankin @ sciencenews