The discovery of brontothere fossils has given scientists a fascinating glimpse into the giant evolution of mammals. These massive creatures, known as thunder beasts, roamed the earth over 35 million years ago and are believed to be the ancestors of modern-day horses and rhinoceroses. Brontotheres were some of the largest mammals to ever walk the earth, with some species reaching over 12 feet tall and weighing up to 2 tons.

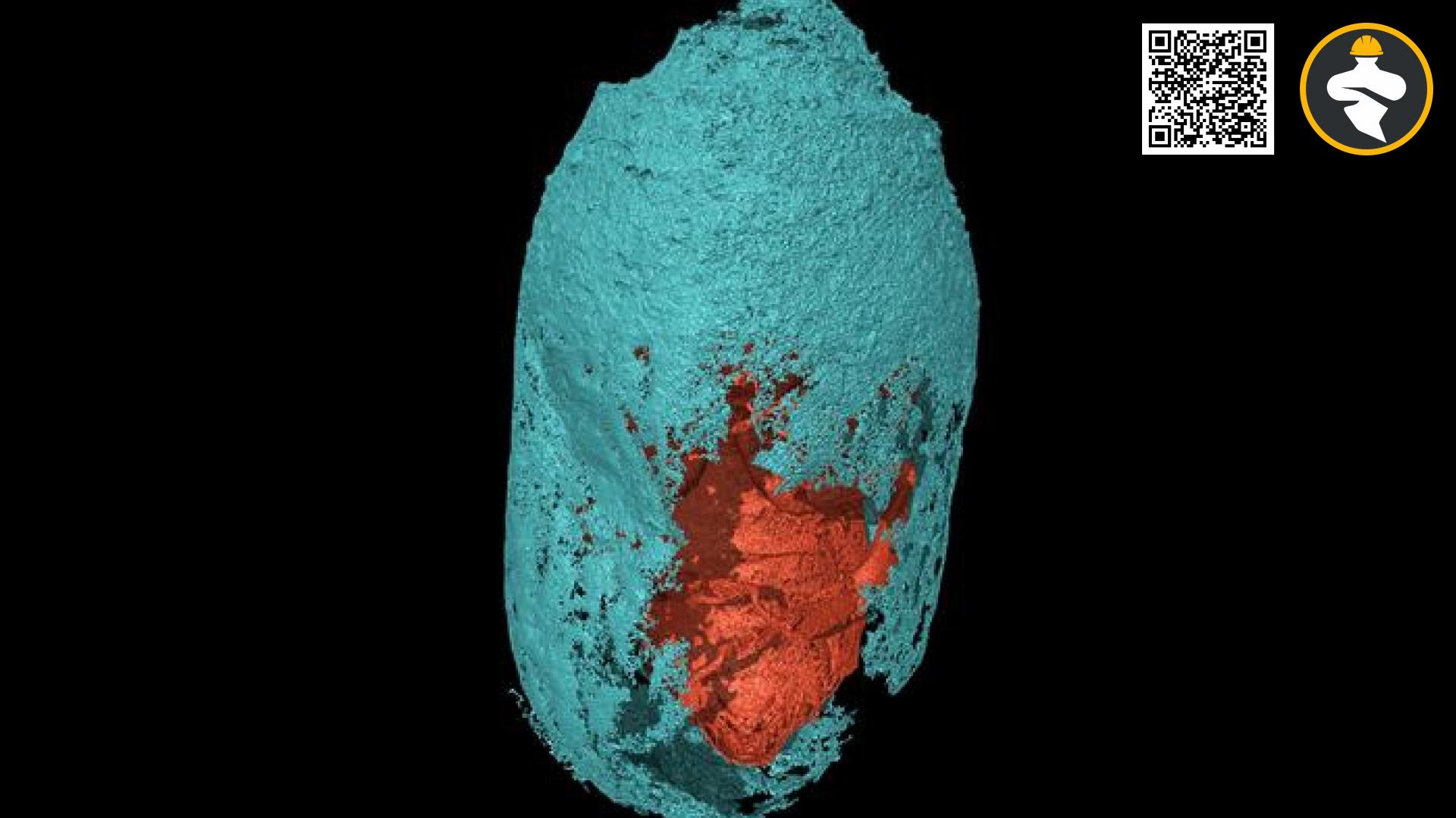

These herbivores had a distinctive appearance, with a large bony protrusion on their snout that resembled a horn or a tusk. Scientists have been studying brontothere fossils for years, trying to piece together how these animals lived and evolved over time. By examining the shape and size of different bones, they have been able to learn about the structure and function of various body parts, such as the legs, feet, and teeth. One interesting finding is that brontotheres likely had a unique way of walking that allowed them to support their massive weight. Instead of walking on the tips of their toes like modern-day horses, these ancient beasts may have walked on the soles of their feet, similar to how elephants walk today. Despite their impressive size and strength, brontotheres eventually went extinct. Scientists are still trying to understand what factors contributed to their downfall, but it may have been due to climate change or competition with other herbivores. While we may never be able to see a brontothere in person, the fossils they left behind continue to fascinate and intrigue scientists and animal lovers alike. By studying these ancient creatures, we can better understand the diversity and complexity of the natural world around us. One interesting aspect of brontotheres is the evolution of their horns. Male brontotheres had much larger horns than females, which they likely used to compete for mates and establish dominance within their herds. Over time, the size and shape of the horns evolved, becoming more elaborate and ornate as the species developed. Another interesting feature of brontotheres is their teeth. These massive creatures had large, flat molars that were ideal for grinding up tough plant material. The shape and size of the teeth varied between different species of brontotheres, allowing them to adapt to different types of vegetation and environments. One of the most intriguing aspects of studying brontotheres is the way they provide a window into the past. By examining the fossils that have been left behind, scientists can learn about the different ecosystems that existed millions of years ago, and how animals adapted to survive in those environments. For example, some brontotheres were found to have lived in forests, while others lived in open grasslands. By studying the bones and teeth of these ancient animals, scientists can learn about the types of vegetation that existed in those ecosystems and how the animals were able to find food and avoid predators. Another fascinating aspect of the study of brontotheres is the way it can help us better understand the evolution of modern-day mammals. By examining the similarities and differences between brontotheres and their descendants, such as horses and rhinoceroses, scientists can gain insight into how these animals have adapted and changed over time. For example, some researchers believe that the brontotheres’ unique way of walking on the soles of their feet may have influenced the evolution of modern-day elephants. While elephants are not closely related to brontotheres, they share some similarities in their anatomy and movement, which may have been shaped by similar environmental pressures. In conclusion, the study of brontothere fossils offers a fascinating glimpse into the diversity and complexity of the natural world. These ancient animals were truly giants of their time, and their fossils continue to captivate and intrigue scientists and animal lovers alike. By studying their bones and teeth, we can learn about the evolution of mammals over millions of years and gain insight into the world that existed long before humans walked the earth.

Reference: Elise Cutts@ https://www.sciencenews.org