A second collection of travel journal entries from a trip to Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil expose the flawed commoner hiding behind the genius. “A perfect traveler does not know his origin; a decent traveler does not know his destination.” One of the smartest sentences ever written or spoken is this one by the Chinese author Lin Yutang (1895–1976).

It effectively suggests that your destination is unimportant. What you discover, however, is what matters. And if you’re lost and unsure of where you’re heading, your vision will become much clearer. It is much more difficult to become a “perfect” traveler in the sense of being completely unbiased; this is because it calls for the complete erasure from memory of one’s background and prior impressions to the point where the traveler’s mind becomes a tabula rasa, capable of perceiving the world as it truly is.

We should consider why a reputable international publisher has just published the second volume of Albert Einstein’s travel journals. This is a follow-up to the brilliantly illuminating “The Travel Diaries of Albert Einstein: The Far East, Palestine, and Spain, 1922-1923,” which I reviewed when it was released in 2018 to widespread praise.

For me, the answer is clear-cut: nothing reveals a person’s personality as completely as the road because, in the words of Jack Kerouac, “the road is life,” and we are all eager to learn what kind of person history’s greatest physicist was, whether we are scientists or not. After reading the earlier collection of Einstein’s travel journals, I came to the opinion that, in addition to being an undeniable scientific genius on the one hand and a man of his time and an average human being, with all his virtues and foibles, on the other.

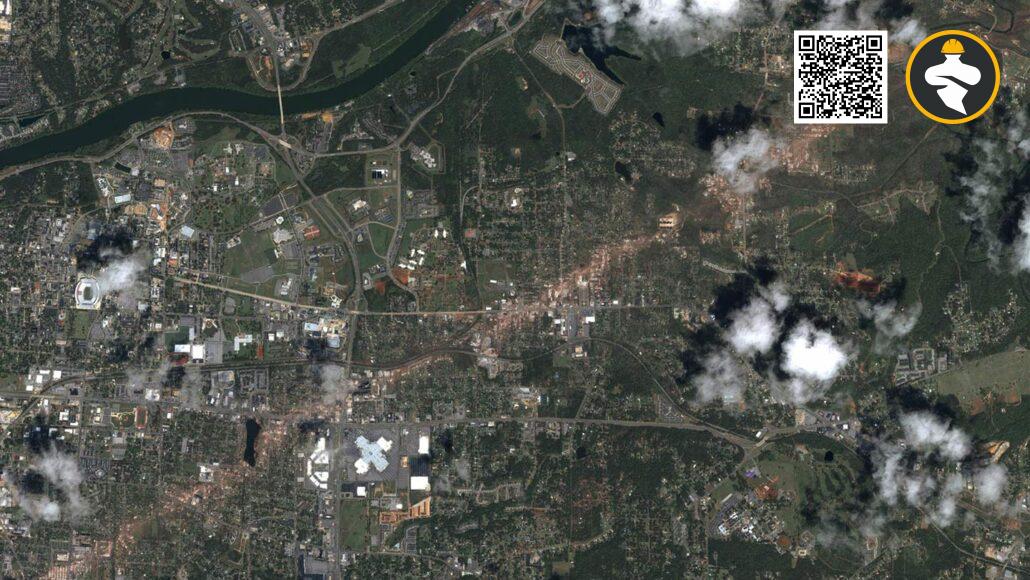

This second volume of “The Travel Diaries of Albert Einstein: South America, 1925,” edited by Ze’ev Rosenkranz and published by Princeton University Press for £28, ISBN 9780691201023, supports the first. It details Einstein’s travels in Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil between March and May. The primary goal of Einstein’s journey was to spread awareness of his theory of relativity among academics and university students in those nations. Also, as the great scientist frequently acknowledges, it served as a form of escape from his rising fame in Germany, where his full-fledged celebrity status had begun to interfere with both his professional and personal life.

According to Rozenkranz’s thorough introduction, Einstein kept a diary in a 72-page lined notebook, but only 43 of those pages included his notes, leaving the other 29 blank. The facsimiled sheets, all 43 of them, combined with a full transcription of Einstein’s own fast and seemingly indecipherable scribbles, as well as numerous images, serve to show the fact that he wrote frequently and frequently in a hurry.

Einstein received a cordial greeting from the local Jewish communities in each of the three nations. Whenever I go, the Jews welcome me with open arms because I serve as a type of symbol for the unity of Jews, he said.

Less hospitable responses came from the scientific groups. Only a very small percentage of “the country’s scientists… was able to follow Einstein’s arguments, and in position to appraise the soundness of the theory,” according to Argentine press reports. And this is what he himself wrote: “In the afternoon, Academy session [in Buenos Aires]. joined as a foreigner. It was hard to stay serious when I was asked very foolish scientific questions.

Students, on the other hand, who by definition are less conservative and are constantly receptive to fresh perspectives, were far more welcoming of Einstein. “First talk in sweltering heat in a packed room. After speaking to a packed house at the Colegio Nacional high school in Buenos Aires, he remarked, “The young are always nice since they are interested in the topics.

Like in the first volume of his diaries, Einstein’s impressions of the places he visited are frequently superficial, naive, and hazy, though not always in a bad way. a couple of illustrations. Buenos Aires is described as a nice and dull city. Humans are cute, innocent, and graceful, yet they are also superficial and opulent. He described Uruguay as “a joyful tiny country, is not only lovely in nature with a warm humid atmosphere, but also has model social structures” when he spoke there at the Montevideo Academy of Engineering.

Like in the preceding volume, Einstein’s most contentious, haughty, and occasionally overtly racist remarks have to do with the people of the nations he visited. From references to “unspeakably ignorant beasts,” “unsavory riff-raff,” and “lacker Indians,” to “sceptically cynical without any love of civilization, debauched in cow fat. According to Ze’ev Rozenkranz, Einstein “seems to have a general distaste” for Argentinians and believes that they are morally and culturally inferior,” which is what the last two remarks about them pertain to.

A little stupidly, Einstein, on the other hand, praises Uruguayans, describing them as “far more human and delightful” than Argentines. “The inhabitants of [Uruguay] simply resemble the Swiss and Dutch. Natural and modest When Einstein arrived in Buenos Aires, he commented, “I’m really bored of people,” which is a tragically conventional small-town attitude. Insofar as he appears to have found himself unable or unwilling to judge them fairly.

But, as a whole, I enjoyed and found the diary to be captivating. It provides a fascinating and unvarnished look into one of history’s greatest minds without idolizing or demonizing it, unlike any movie or literary biography. As Rozenkranz so eloquently puts it: “…like us all, Einstein had the right to be incorrect and to make potentially self-destructive mistakes. He becomes even more human as a result.

Hear, hear…

Returning to the Lin Yutang quote from the beginning, what kind of traveler was Einstein, really? The ability to get lost, as his journals attest, is the primary characteristic of a successful traveler, and as I frequently remind the students in my travel writing seminars, this man frequently felt truly lost (read: confused) while on the road.

While he continued to be a wonderful scientist, he had never developed into a “perfect” traveler because, like the majority of us (including this writer), he was unable to entirely shed the heavy luggage of his past and attain an unbiased vision of the world. “South America, 1925” is the second of six trip journals written by Albert Einstein that will be published. I’m eager to get my hands on the last four.

Reference: Vitali Vitaliev @ eandt.theiet.org