Onshore wind has experienced a bit of a time warp in the UK. Since 2015, when the UK government tightened planning regulations governing the technology, only a small number of new onshore wind farms have been constructed in England. This has prevented new projects. Scotland plans to treble its onshore wind capacity by the end of the decade (devolved nations have separate requirements). That indicates that many of the wind turbines scattered over the English countryside are at least ten years old and, to be honest, are rather worn out.

From this vantage point, it would be simple to believe that the wind energy sector is a slowly evolving one and that turbines erected 25 years ago still resemble those coming off assembly lines today.

Historically, a variety of materials have been used to construct wind turbines. The blades are often composed of epoxy or polyester reinforced with fiberglass, whilst the towers are typically built of steel or concrete.

Problematic materials

Producing steel towers requires a lot of energy, and since most of the blades can’t be recycled, they frequently wind up in landfills after their useful lives.

The issue of size is also present. Although taller turbines may capture wind more effectively, steel tower building costs rise with height. The more substantial the towers, the more expensive a problem it is to transport and install the turbines.

Due to this issue, wind energy businesses have begun to develop better turbines.

Wood towers

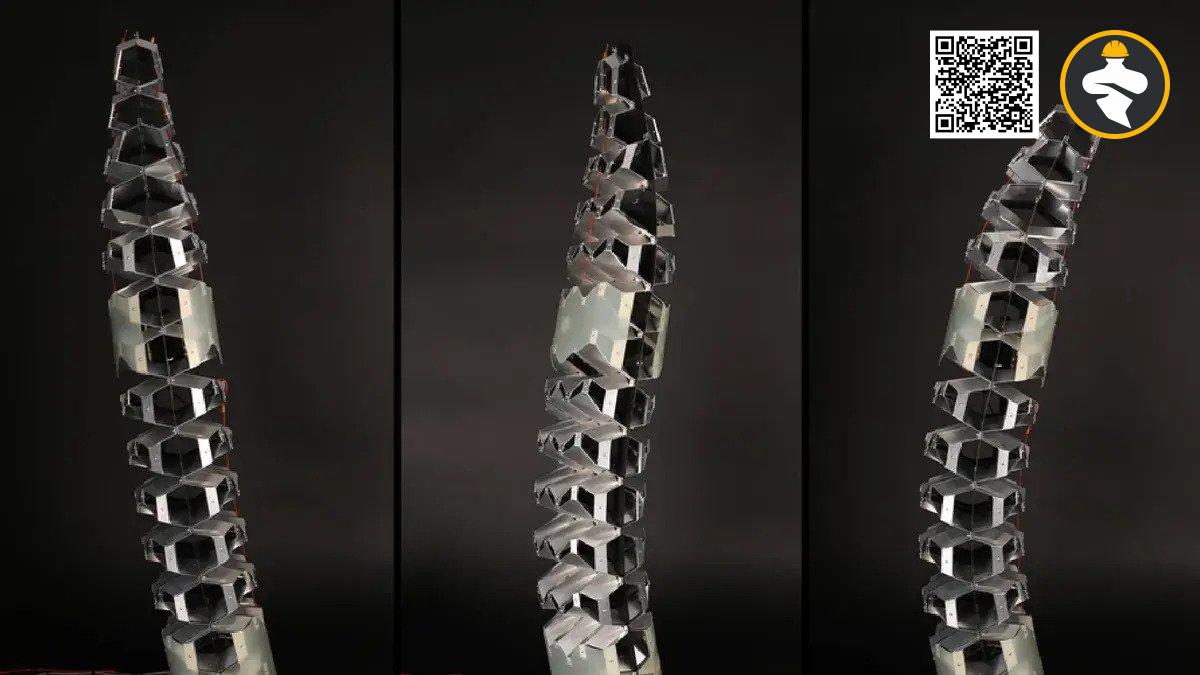

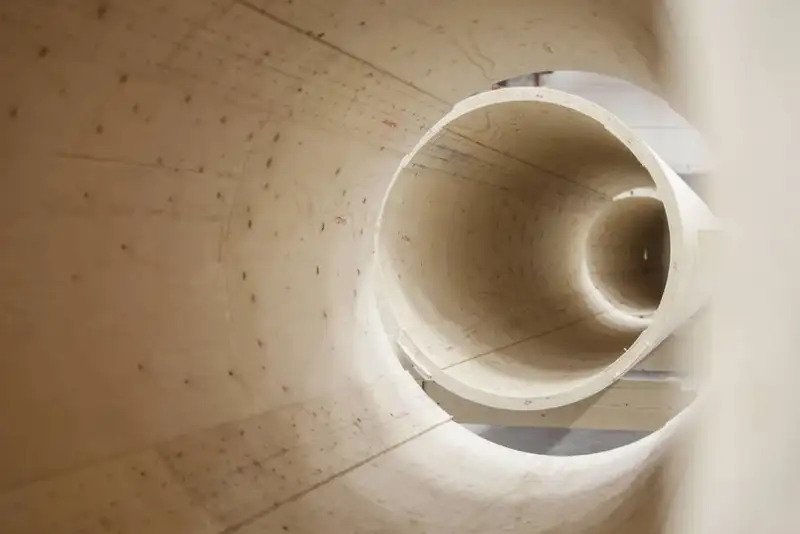

Nordic startup A method for building turbine towers out of laminated wood parts has been devised by Modvion.

Timber towers can be built in parts and slotted together on location, making them lighter than steel. According to Erik Dölerud, an engineer at Modvion, this makes taller, more potent turbines more affordable and convenient to carry. According to him, “the entire market is moving toward big towers, and the taller the towers go, the more significant this fundamental advantage of timber becomes.” “So, for certain setups, it’s clearly a cost-effective choice.”

Additionally, according to Modvion, manufacturing a timber tower rather than a steel one results in 90% fewer carbon dioxide emissions.

Additionally, the modular tower portions can be reused when the turbine reaches the end of its useful life.

Varberg Energi is currently working on a 100-meter-tall turbine that should open the door for the commercial rollout of timber towers when it is finished next year. The towers could eventually soar as high as 150 meters. In the 2030s, Dölerud says, “the ultimate goal is to be a top global supplier of wind turbine towers.”

Timber blades

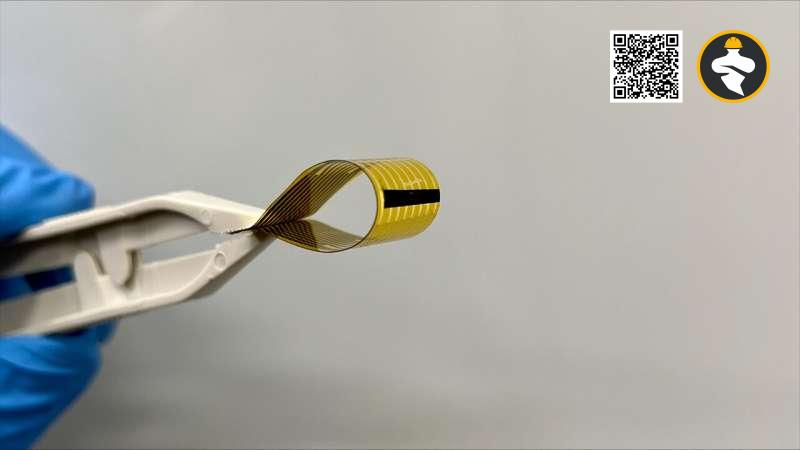

Meanwhile, German start-up Voodin Blades has a vision for wind turbines to be built with wooden blades, which are lighter and easier to dispose of than fibreglass blades.

It is building its first 20-metre-long blades, which will be installed on a test turbine with a capacity of 0.5 megawatts in Warburg, Germany, by the end of the year. Work is also underway on an 80-metre-long blade that could be fitted to a turbine up to 6 megawatts in capacity, the size used in commercial farms.

The business announced a collaboration with Stora Enso, a Finnish company that produces paper, pulp, and other forest products, in November. The blades are being made from laminated veneer timber (LVL) from Stora Enso.

In terms of strength per unit of weight, Stora Enso, which also provides lumber to Modvion, claims that its LVL is twice as robust as steel and can perform just as well as fiberglass in a turbine blade. Saki Boukas, who is in charge of Stora Enso’s timber division, describes this material as “strong, lightweight, and self-replicating.”

Eventually, according to Dölerud, turbines might be constructed using timber towers and blades. He declares, “I think it’s a very good concept. “I believe there should be more uses for structural timber than there now are. It should be used for more advanced engineering applications because it is an advanced engineering material.

Stumbling blocks

What then is the catch? According to Boukas, persuading risk-averse engineers to gamble on timber presents the toughest hurdle. In terms of technology, I don’t see any problems. Technology is well-known, and everything is rather obvious. More so, new technology is entering the market, and before people can completely accept it, they need to feel, touch, and smell it, he claims.

Nevertheless, John Hall of the University at Buffalo in New York believes the concept of wooden turbines is promising – not least because the steel sector will be under a lot of strain as a result of the enormous demand for wind turbines in the future decades. By the end of the decade, the value of the worldwide wind turbine market is predicted to double, making it difficult for the steel industry to keep up.

The industry may be “risk adverse” by nature, he claims, but if materials are scarce, that will swiftly change. He asserts that the industry will be open to innovation “if [it] starts to encounter shortages or anything that is going to hinder its expansion.”

Reference: Madeleine Cuff @ www.newscientist.com