Research on solar geoengineering has some academics concerned that it would normalize a hazardous and poorly understood technique. However, proponents assert that any measure that can slow down climate change warrants further study.

Imagine that it is the year 2025. Northern India has seen a heatwave unlike any other, with temperatures reaching the 40s and oppressive levels of humidity that prevent people from perspiring sufficiently to cool themselves.

People who cannot afford air conditioning urgently leap into lakes to cool down, but for the most, it is ineffective. Twenty million individuals die each year. More people have died due to climate change in recent weeks than during World War One.

Supporters concede that spraying substances into the sky to chill the world seems a little far-fetched but still maintain that reducing emissions should be the principal focus.

However, the data suggest that solar geoengineering should be compelling and might be a last-ditch measure to avert catastrophe as the century goes on, so it at least has to be researched. However, because the technology is so contentious, it is challenging to obtain funds. Due to the local opposition, a recent, well-publicized outdoor experiment was canceled.

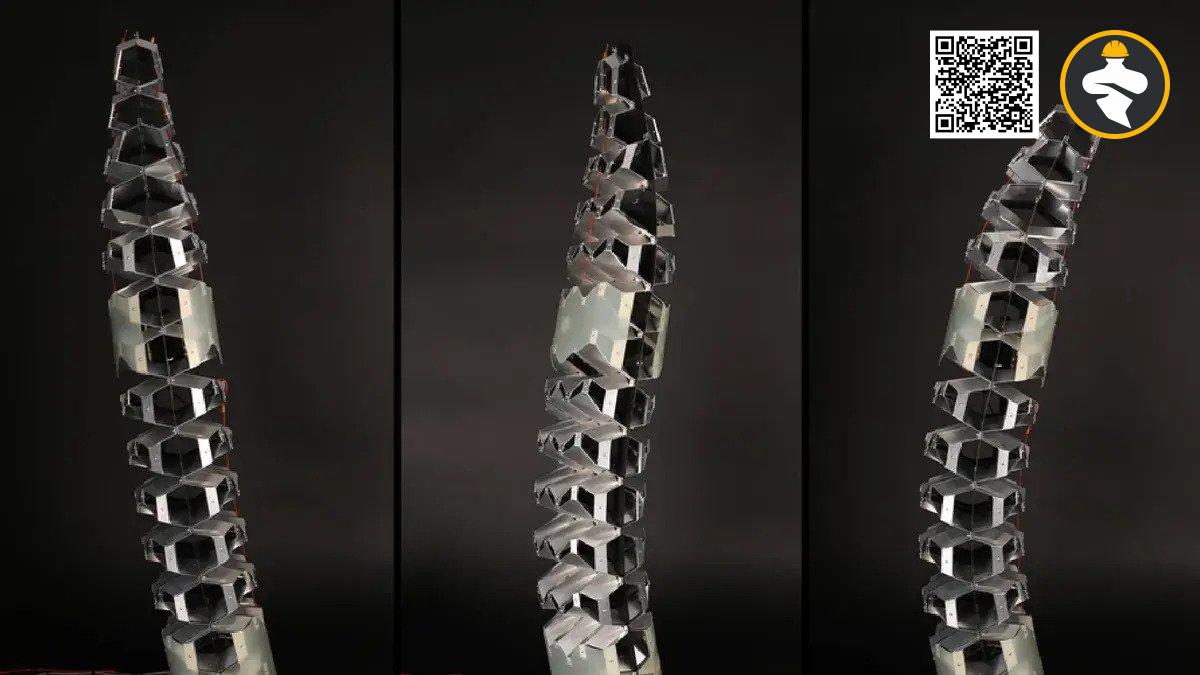

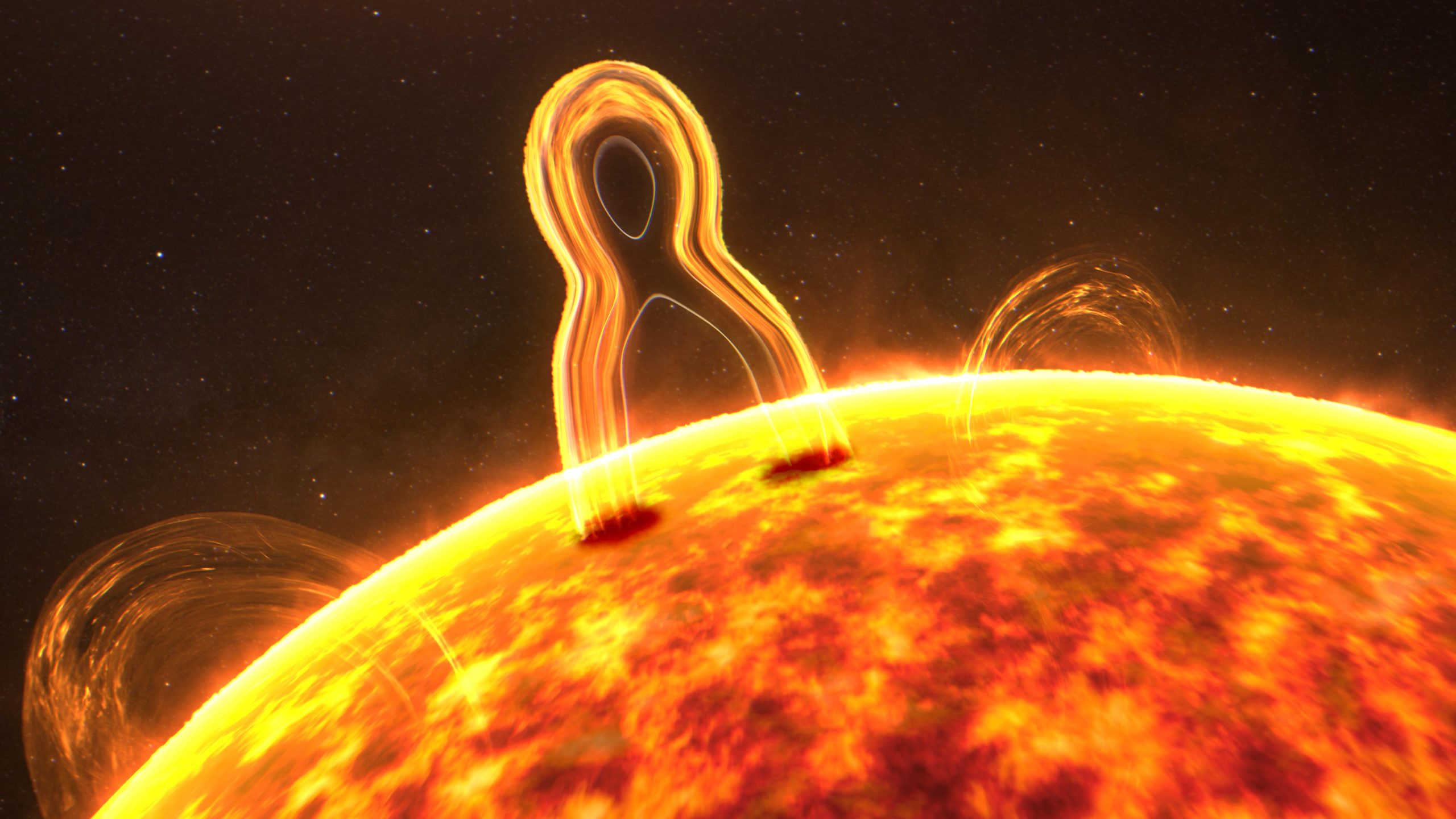

The goal of all solar geoengineering techniques is to reflect sunlight. Spraying sea salt on marine clouds to make them brighter is one of them, as is altering crops to make them more reflecting.

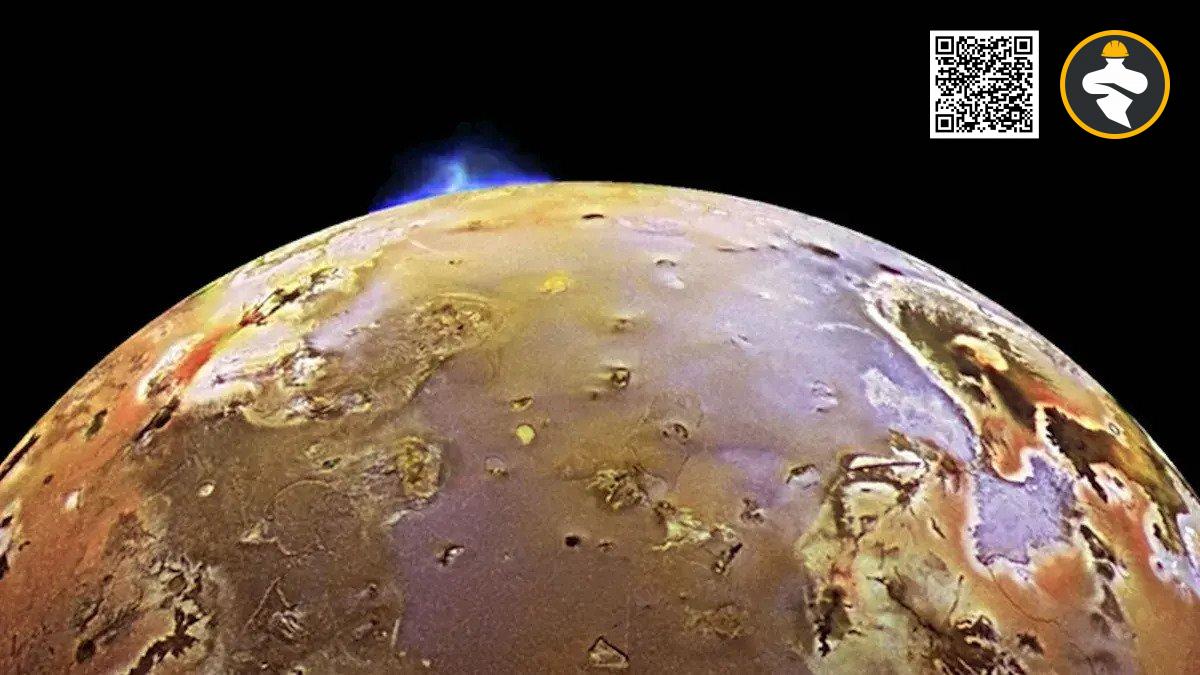

But stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), which aims to imitate the aftermath of a volcanic explosion, is the providing good and most practical method. After Mount Tamboro in Indonesia erupted in April 1815, spewing volcanic ash around the globe and generating such dreadful weather in Europe that a young Mary Shelley was locked up inside writing Frankenstein, 1816 became known as the “year without a summer.”

The IPCC continues to be undecided in the draft of its most recent reduction study, which was published recently, stating that modeling studies suggest SAI might lower surface temperatures and certain climate change hazards, but at the same time, it could potentially create a variety of new dangers.

Advocates contend that if trials and modeling revealed that SAI had significant hazards, additional research would actually reduce the likelihood of deployment. In other terms, if the risks of SAI are well outlined, a needy country affected by climate change might think twice before taking the risk.

Even though the investigation is ongoing IPCC lists hundreds of modeling studies conducted since 2014—there are still limitations.

The Harvard project’s planned balloon test flight in Sweden was put on hold in 2021 because of opposition from environmentalists and the Saami people, who fear it will help normalize the technology.

Another balloon test flight was canceled in the UK in 2012 because of concerns about a potential commercial conflict of interest and the absence of a governance structure that would have controlled such operations.

Even if we ultimately come back at 1.5C at the end of the century, Abécassis added, “there’s a substantial likelihood that we exceed.” However, it is vital to “examine if [SAI], among others, may be an alternative.” Emission reduction “must remain the core strategy.”

However, the Global Commission on Governing Risks from Climate Overshoot cannot reveal its conclusions until early 2024, then which should begin operations later this year.

Reference: David Matthews@ sciencebusiness.net