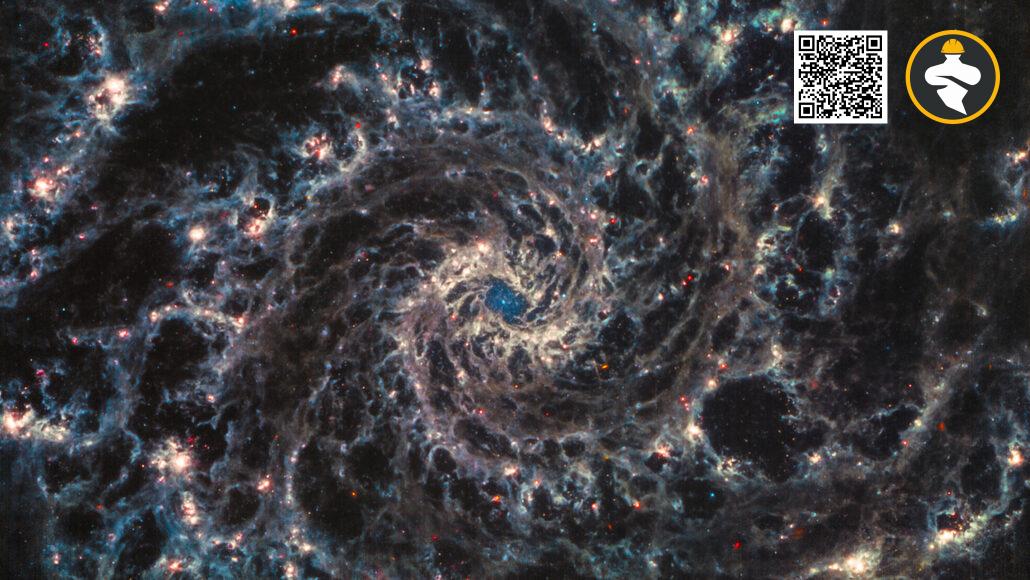

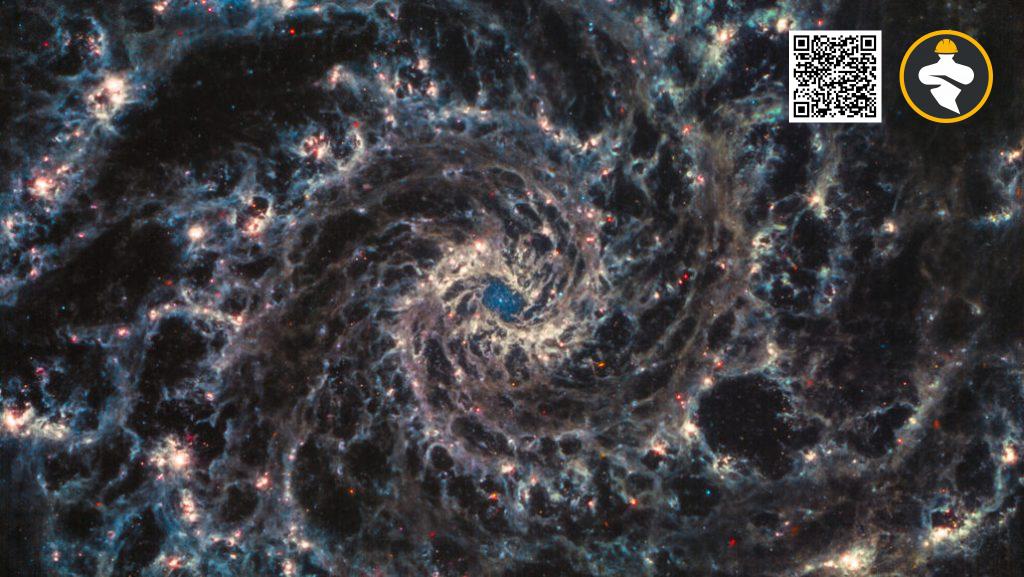

In new photos from the James Webb Space Telescope, a swarm of galaxies sparkles with detailed detail. JWST’s sensitive infrared eyes are revealing how newborn stars influence their environment, demonstrating how stars and galaxies grow up together.

“We were really blown away,” says Janice Lee, an astronomer at the University of Arizona in Tucson. In a special February edition of Astrophysical Journal Letters, she and more than 100 astronomers reported on scientists’ first glimpse at these galaxies with JWST.

Lee and her colleagues chose 19 galaxies that, if viewed with the JWST, may disclose new data about star life cycles.

These galaxies are quite close to the Milky Way, approximately 65 million light-years, and they have different spiral structures. The crew had used several observatories to study the galaxies, but sections of the galaxies had always seemed flat and featureless.

“We’re seeing structure down to the absolute tiniest scales with [JWST],” Lee explains. “We’re witnessing the youngest locations of star formation in many of these galaxies for the first time.”

The faces of the galaxies are pockmarked by black gaps among bright filaments of gas and dust in the new photos. Comparisons to Hubble Space Telescope photos indicate that these spaces are bubbles carved out of the gas and dust by high-energy radiation from nascent stars in their cores.

As the most massive of those stars die and burst, the gas is pushed out even more. Several of the bigger bubbles include tiny bubbles on their rims, which might suggest areas, where gas pushed by dead stars, has begun to form new stars.

Studying these processes in various types of spiral galaxies will help astronomers understand how the forms and features of the galaxies impact the life cycles of their stars, as well as how the galaxies expand and change with their stellar residents.

“We’ve just explored a few [of the 19 chosen galaxies,” Lee explains. “We need to investigate these phenomena in a large sample size to understand how the environment changes… how stars are formed.”

Reference: Lisa Grossman@www.sciencenews.org