Mamadou Ngulo Konaré told a legendary occurrence from his childhood UNDER THE SHADE OF A MANGO TREE. Well, drillers had visited his Mali hamlet of Bourakébougou in 1987 in an attempt to find a water source, but they had given up after one dry borehole at a depth of 108 meters. Denis Brière, a petrophysicist and vice president at Chapman Petroleum Engineering, was informed by Konaré that “meanwhile, the wind was blowing out of the hole” in 2012. The wind erupted in his face as one driller looked into the hole while puffing on a cigarette.

He wasn’t killed, but he was scorched, said Konaré. And then there was a massive fire. During the day, the fire had a color similar to that of brilliant blue water and was free of pollution from black smoke.

We could see each other in the light throughout the fields since the fire’s color was like gleaming gold at night. We were genuinely concerned about the destruction of our village.

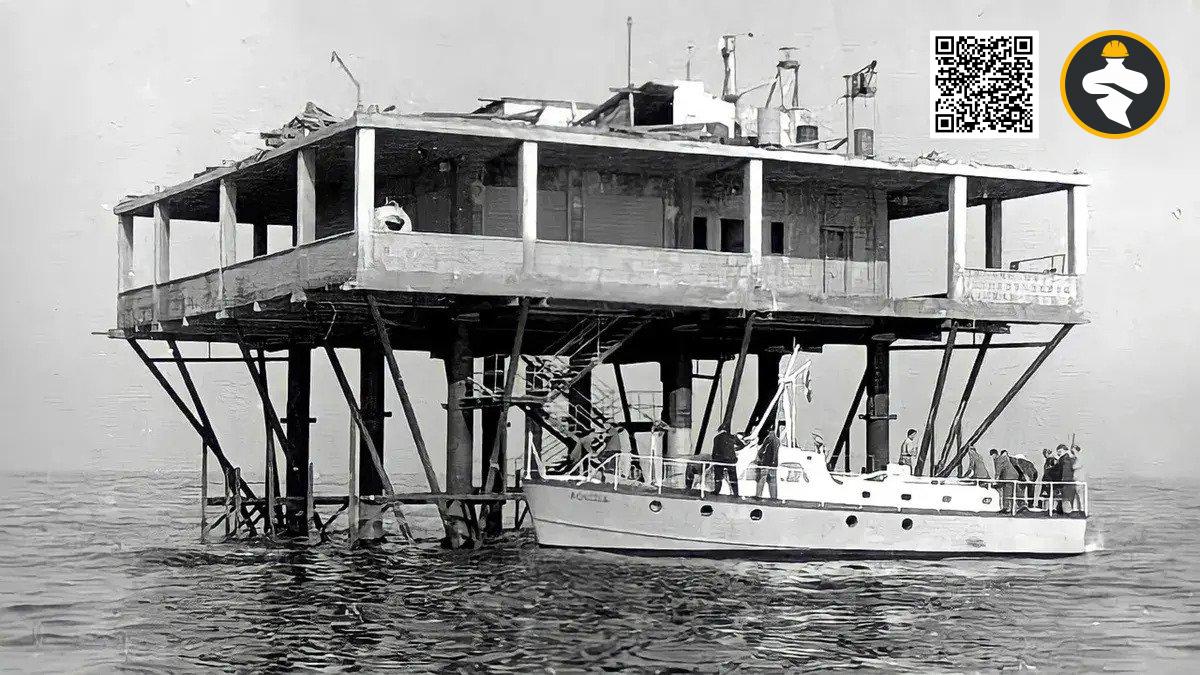

To put out the fire and cap the well, the crew needed several weeks. And until 2007, the villagers avoided it there. At that time, wealthy Malian politician, businessman, and head of the oil and gas corporation Petroma, Aliou Diallo, gained the right to prospect in the area surrounding Bourakébougou. Humans are formed of dirt, but the devil is made of fire, according to a local proverb, Diallo. “The location was cursed. I responded, “Oh, cursed places, I prefer to transform them into a blessing one.”

He hired Chapman Petroleum in 2012 to find out what was coming from the borehole. Brière and his staff found that the gas contained 98% hydrogen while they were protected from the 50°C heat in a mobile lab. That was extraordinary because hydrogen was not supposed to exist very much inside the Earth and hardly ever shows up in oil operations. Brière relates that on that day, “we had celebrations with big mangos.”

Brière’s team fitted a Ford engine modified to consume hydrogen in a matter of months. It emitted water as waste. The engine was connected to a 300 kW generator, which provided Bourakébougou with its first electrical conveniences, including flat-screen TVs for the village chief to watch soccer, freezers to create ice, and lighting.

Test results for kids also became better. Before coming to class in the morning, “they had the lighting to absorb their studies,” adds Diallo. He quickly gave up on oil, renamed his business Hydroma, and started drilling new wells to estimate the amount of subsurface supply.

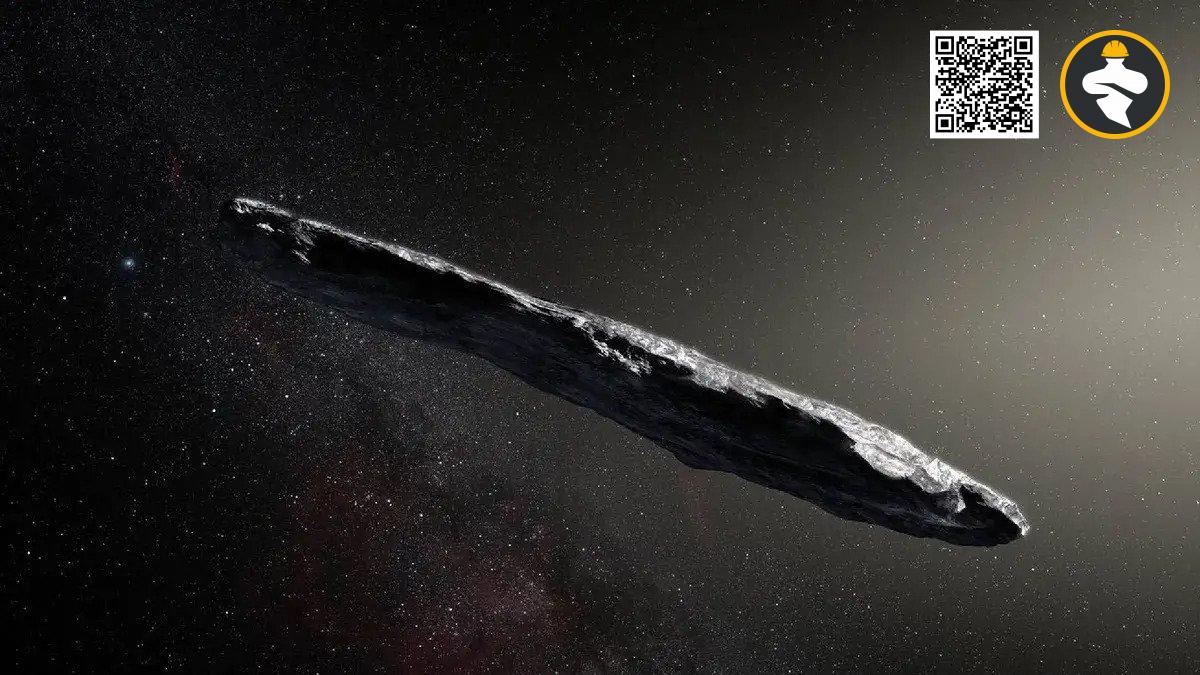

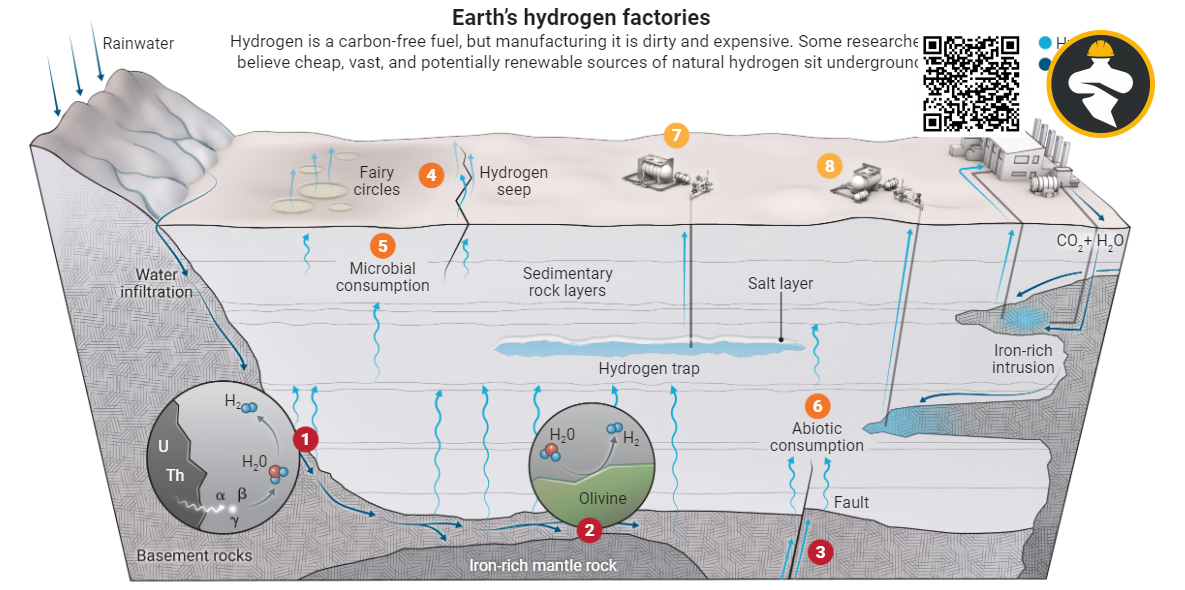

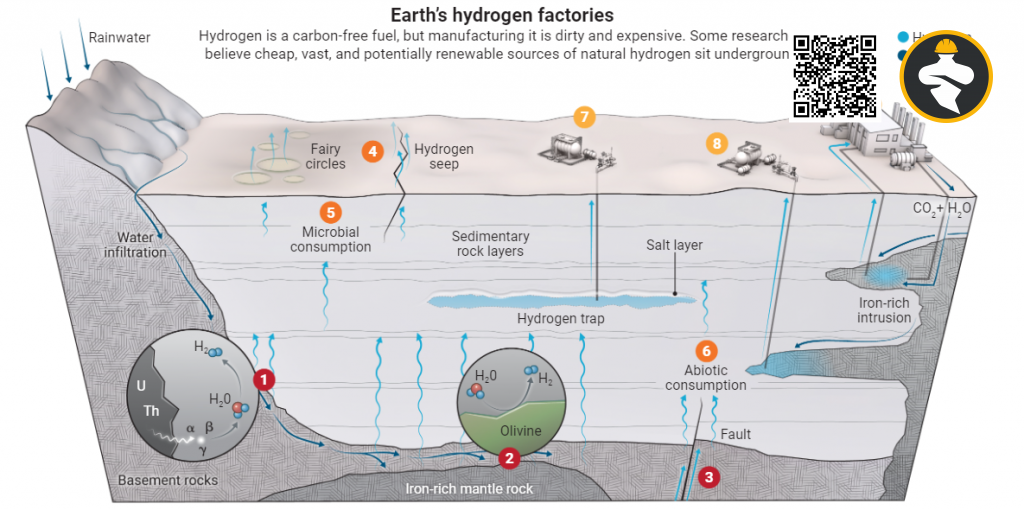

The Malian discovery was compelling proof of what a small team of scientists who had been examining clues from seeps, mines, and abandoned wells had been arguing for years: that, contrary to popular belief, there may be vast reserves of natural hydrogen all over the world, similar to those of oil and gas, but not necessarily in the same locations. According to these scientists, hydrogen is continuously produced by water-rock reactions deep under the Earth and percolates up through the crust, occasionally accumulating in subsurface traps.

A U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) model presented in October 2022 at a meeting of the Geological Society of America suggested that there might be enough natural hydrogen to satisfy the expanding world need for thousands of years.

Natural hydrogen is still in its infancy. Scientists are unsure of how it arises, migrates, and—most significantly—whether it builds up in a way that may be used for economic gain. Geophysicist Frédéric-Victor Donzé of Grenoble Alpes University says, “Interest is developing quickly, but the scientific facts are still lacking.” Big Oil is observing from a distance as wildcatters engage in the perilous exploratory job. Only a few exploration wells have been sunk abroad, and the commercialization of the Mali field has encountered difficulties. Donzé, who has vowed not to accept funding from the sector, is concerned about hype.

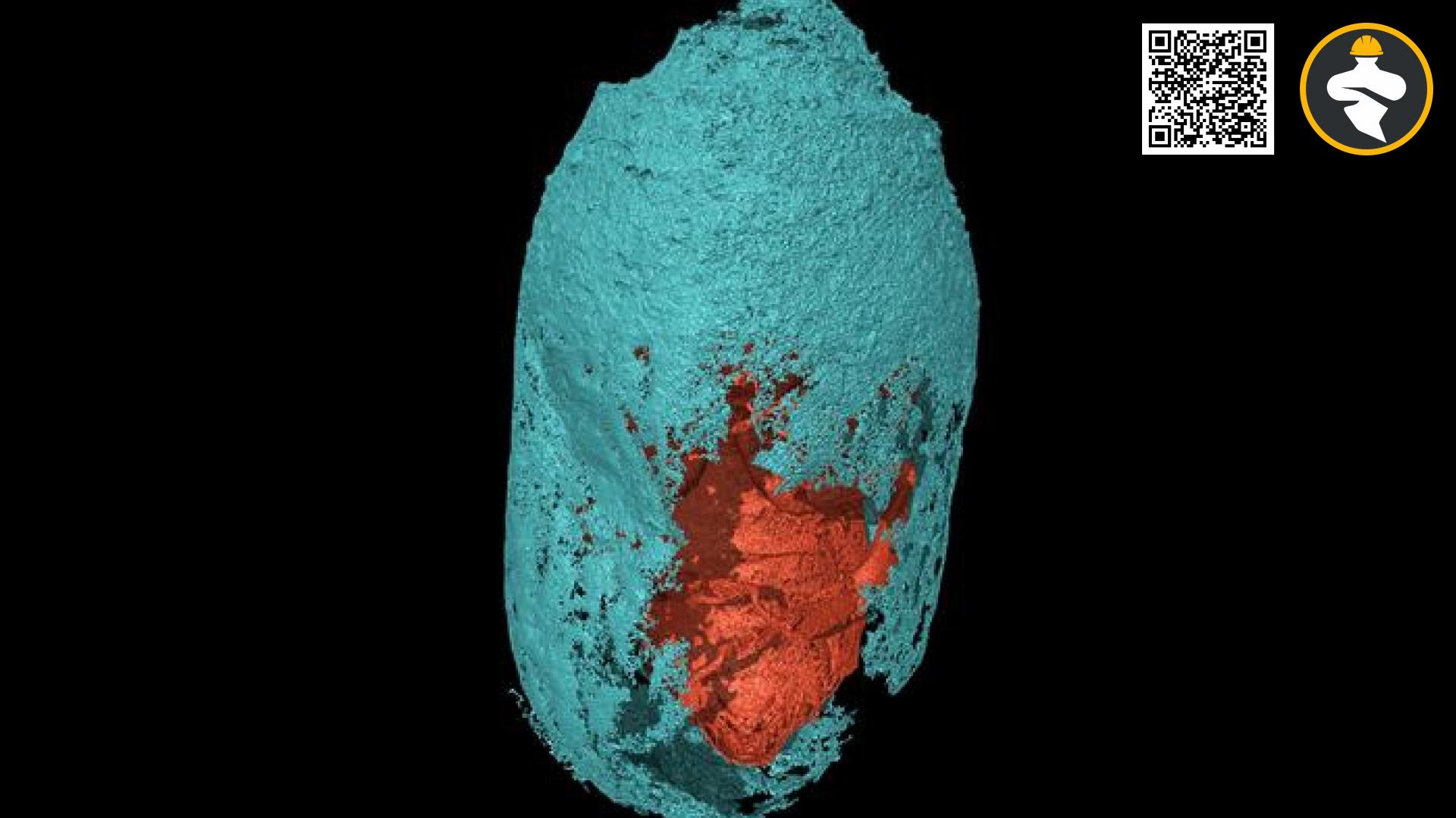

The recoverable amount in a reservoir is referred to in the oil industry as “the prize,” and Brière claims he can now properly evaluate it after drilling 30 wells across the Bourakébougou field. He claims that the field is vast: It has roughly 5 million tons, or 60 billion cubic meters, of hydrogen trapped behind wide-spreading horizontal ledges of old volcanic rock.

Yet, the value of the award can be underestimated. According to Brière, a reservoir’s volume is less important because Earth produces hydrogen at a rate that is far faster than it does oil. We don’t perceive it as a contained volume; rather, we perceive it as continuously filling and flowing. The Bourakébougou field and similar ones might potentially be exploited for many years without running out of resources.

According to Brière, “We’ll be caring for our generation and our children’s children’s generation.”

Indeed, the residents of Bourakébougou hope so. A recently installed fuel cell—quieter and more effective—has not yet been connected to the local grid while the Ford engine continued to run until its spark plugs failed a few years ago. While awaiting the arrival of a hydrogen future, Bourakébougou is gloomy.

Reference: Eric Hand@www.science.org