Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have discovered that quicklime, a key ingredient in ancient Roman concrete, may have given the material self-healing properties, contributing to its durability. The research could improve the performance of modern concrete, which typically consists of a mixture of limestone, clay, sand, chalk, and other ingredients and starts to crumble in as little as 50 years. Ancient Roman concrete, made from a mixture of slaked lime, tephra, and water, was used on a mass scale in construction projects by 200 B.C.E. and is still standing today.

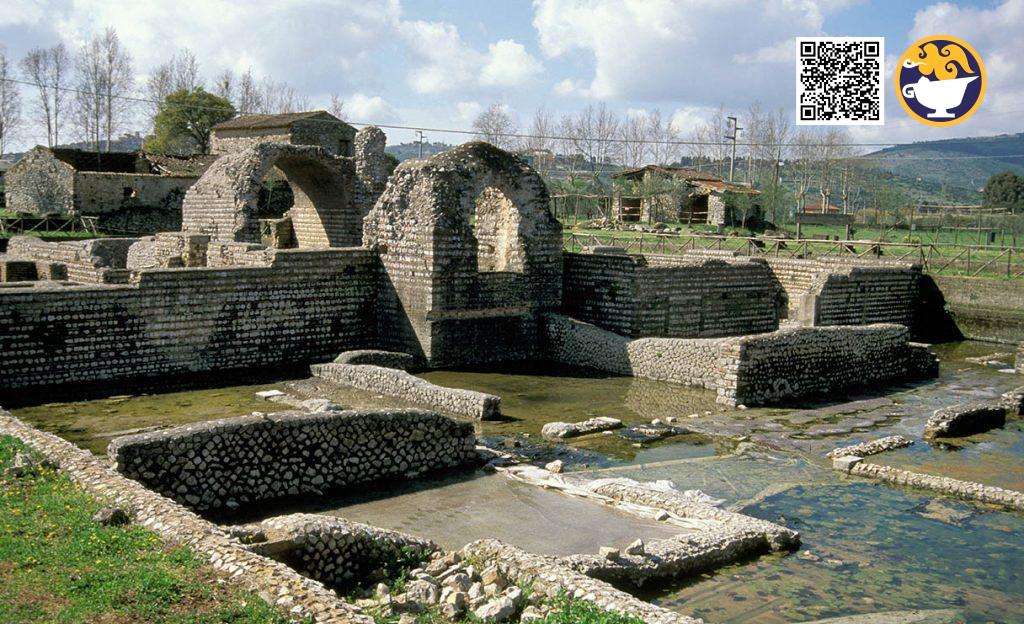

The ancient Roman Empire is known for its impressive engineering feats, many of which are still standing today. Bathhouses, aqueducts, and seawalls built more than 2000 years ago are a testament to the durability of Roman concrete, a material that has proven far more resilient than its modern counterpart. Modern concrete, which is typically made from Portland cement, a mixture of limestone, clay, sand, chalk, and other ingredients ground and burnt at high temperatures, starts to crumble in as little as 50 years. In contrast, Roman concrete, made from a mixture of slaked lime, tephra, and water, was used on a mass scale in construction projects by 200 B.C.E. and is still standing today.

Researchers have long been trying to understand why Roman concrete is so long-lasting. In 2017, for example, a team of scientists found that seawater reacting with the ingredients of the concrete created new, tougher minerals, at least for structures exposed to the ocean. But there may be other explanations as well.

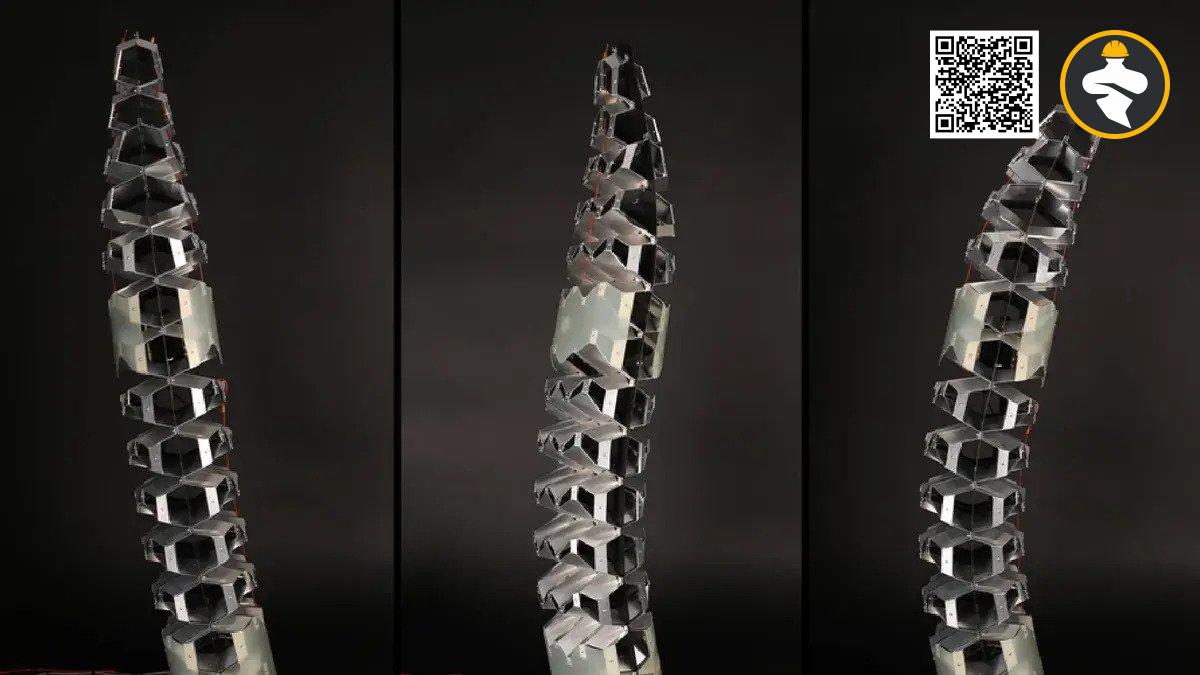

A recent study by scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) suggests that quicklime, a key ingredient in ancient Roman concrete, may have given the material self-healing properties. Quicklime, also known as calcium oxide, is produced by heating limestone to high temperatures in a kiln. When it is mixed with water, it undergoes a chemical reaction, releasing heat and producing a white powder known as slaked lime, which is one of the main components of Roman concrete.

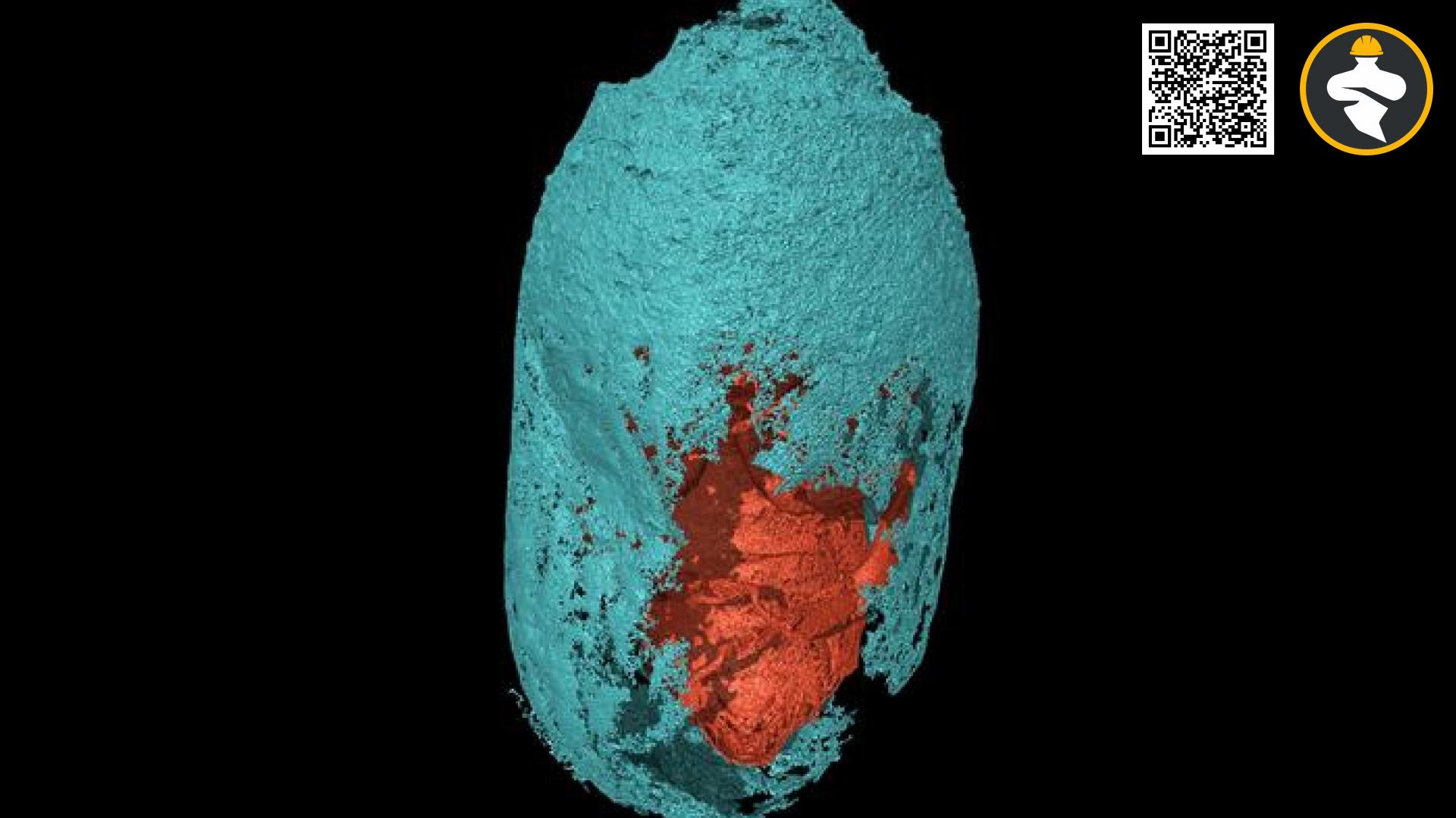

To investigate the potential self-healing properties of quicklime, the MIT team gathered concrete samples from an ancient city wall in Privernum, a 2000-year-old archaeological site near Rome. In the lab, they focused on small calcium deposits embedded in the concrete, known as lime lumps. These lime lumps, they found, contained a mineral called tobermorite, which is known to have self-healing properties.

The researchers believe that when cracks form in the concrete, water and carbon dioxide from the air enter the material and react with the quicklime, forming a new layer of tobermorite on the surface of the crack. This seals the crack and prevents further damage to the concrete.

The findings of the MIT study could have significant implications for the design and performance of modern concrete. By understanding the mechanisms behind the self-healing properties of Roman concrete, engineers may be able to develop new strategies for improving the durability and longevity of concrete used in construction today.

Marie Jackson, a geologist who studies ancient Roman concrete at the University of Utah but was not involved in the MIT research, commented on the potential impact of the study: “The work could help engineers improve the performance of modern concrete.”

The Romans were not the first to invent concrete, but they were the first to employ it on a mass scale. By 200 B.C.E., concrete was used in the majority of their construction projects. Roman concrete consisted of a mixture of slaked lime, small particles and rock fragments called tephra ejected by volcanic eruptions, and water. Tephra, also known as volcanic ash, is a fine-grained, porous material that is rich in silica and alumina. When it is mixed with slaked lime and water, it forms a paste that hardens over time, creating a strong and durable building material.

In addition to the potential self-healing properties of quicklime, the use of tephra in Roman concrete may also have contributed to its longevity. Tephra is highly resistant to chemical attacks, and the porous nature of the material allows it to absorb water, which can help to prevent the concrete from cracking due to the expansion and contraction caused by changes in temperature and humidity.

Despite the many advantages of Roman concrete, it was not widely used after the fall of the Roman Empire, and it was not until the 1800s that concrete was rediscovered and used on a large scale in modern construction. Today, concrete is the most widely used building material in the world, and it plays a vital role in the infrastructure of cities and towns everywhere. However, the durability of modern concrete remains a challenge, and engineers are constantly searching for ways to improve its performance. The findings of the MIT study on the potential self-healing properties of ancient Roman concrete could provide valuable insights for the development of more durable and long-lasting concrete in the future.

reference: JACKLIN KWAN @ https://rb.gy/vlpcwr